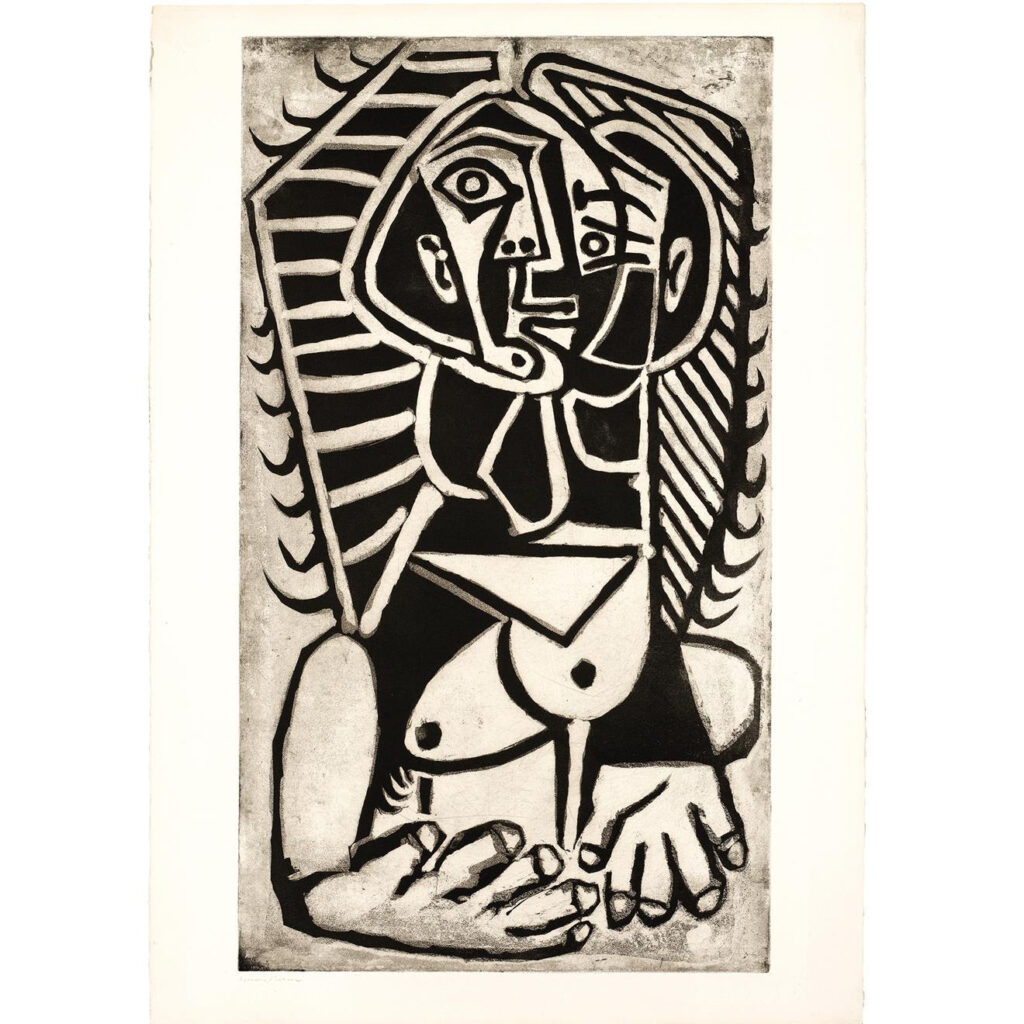

With few exceptions, Picasso’s portraiture focused on storytelling rather than realism. Just glancing at L’Egyptienne confirms this. Created in the 1950s, as Picasso approached his later years, this image harkens back to his early days of African-inspired Cubism. Particularly, it calls to mind Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), one of his most famous works. This large-scale painting tells the story of entering a brothel with a twist. Its scene and characters exist in the artist’s imagination. Picasso fused together a potentially real-life experience living in the seedy Montmartre quarter of Paris with the sculptural style of African “fetish” art* to create one of his most famous graphic works. L’Egyptienne, though fifty years later, demonstrates Picasso’s evolution as a Cubist with an even more personal perspective.

Picasso’s interest in African art as a mode of abstraction began at the dawn of the twentieth century.** Ancient Egyptian portraits, more specifically, acted as a form of political propaganda at times, foregoing a realist sense of scale to instead use proportion and shape to convey themes like the power of a ruler or a god. This non-western approach to dimension and shape defied any sense of realism and allowed him to show a greater visual truth “than the mere representation of what the eye saw.”***

L’Egyptienne embraces the cultural practice ancient Egyptians are most remembered for: mourning the dead. Picasso’s relationship with Françoise Gilot was only months from dissolving. Gilot was spending months at a time in Paris, working on sets for a ballet. Her independent spirit was once attractive to Picasso but after a nearly decade-long affair he no longer found it endearing. In fact, her extended stay in Paris infuriated him and led to the creation of L’Egyptienne. Its fragmented, high-contrast rendering resembles a sarcophagi, which is why printer Lacourière named it as such. Whether this memento mori comparison was intentional or subconscious, it seems like more than a coincidence.

From a technical point of view, this print is also exemplary of Picasso’s supreme technical ability. He used sugar-lift aquatint, a highly delicate process not typically used on a plate as large as the L’Egyptienne. Not only is the scale impressive, but so is the depth of the black shades. Inspired by Rembrandt, Picasso sought to replicate the great master’s deep pitch shades and in doing so cemented himself as a true successor. As for Picasso’s personal life, Gilot left him shortly after this print was created, the only one of his muses to take matters into her own hands. L’Egyptienne captures her strength rather than her beauty, memorializing their relationship as perhaps he wanted to remember her.

Courtesy of John Szoke Gallery.