Statement: Three Cinderellas, one diamond ring, and a pair of glass slippers: Ricard paintings inspired by the artist’s famous friends and infamous life lay fantasy on thick with a side of acid pragmatism, paying fairy tale homage to Andy Warhol’s iconic shoe sketches.

He acted in underground films, playing Warhol in the artist’s own Andy Warhol Story. He became a renowned poet and writer, published in the Paris Review and Artforum. In typically wry fashion he explained how he became an painter: “I began adding images [to my poetry] because I’ve always liked to draw and paint. And it was hard to find junk-store paintings of the right quality, things that could support some writing, so I just started making the images myself. Unfortunately, people really like that, even though I far prefer just the writing.” Ricard drew on his vast knowledge of literature and art history, weaving these references together with bursts of autobiographical poetry: what the New York Times termed his “seething verbal finesse.”

Ricard, having spent years in the Factory’s milieu, learned from Warhol’s creative strategies. Warhol created images quickly with screen printing, with no regard for perfection. Duplication was the method and the ideology. Ricard, too, worked quickly: urgency was part of his visual language of looped cursive and scribbled colors. He often borrowed a lithographic plate or silkscreen from already-completed works, printing the matrix on canvas or paper to create backgrounds for new works (Size 3’s red printed background may be an example of this). He appropriated thrifted paintings and discarded items such as a pinboard or a piece of insulation, so long as the object in question had a flat surface upon which to work. The two artists were both outsiders to the art world in a sense—Warhol coming from the world of design and Ricard, a bona fide author, but both intuitively understanding how to compel the viewer.

As Warhol anthologized consumerism, Ricard catalogued desire. For example, Size 3 and One Shoe One You feature Ricard’s take on Warhol’s famous shoe drawings which the artist produced in droves. The shoes are labeled with socialites’ and celebrities’ names or by a short musing description. By removing each shoe’s partner, both artists elevated the single shoe into the symbolic realm: for Warhol, each shoe was a character representing an individual, but was also broadly denoting culture. Ricard placed his shoe in the context of Cinderella’s story: a young woman who is orphaned and left to the devices of her evil stepmother. Cinderella is saved after Prince Charming finds her shoe, left behind as she fled the ball at midnight. It’s a story of sadism and suffering, transformation and luck, of late-night parties and hurried exits—very Rene. One Shoe One You reproduces the iconic Disney animated version of Cinderella, with her blue dress, updo, and choker, in olive green and dark grey paint. Around her doubled shadow float a diamond ring and glass slipper. Cinderella stripped of romance is the compact oil paint stunner Whore: with pragmatic musing about a sex worker, pictured in glamorous pink and silver.

Perhaps Ricard could imagine himself as the tragic fairy tale character out past midnight. The artist loved to wear rings and flamboyant fashion. He could be found hobnobbing in the glittering nightlife scene with Andy Warhol and Basquiat, socialites and celebrities, and the next moment stalking the east village in search of a fix or nodding off on endless early morning train rides. Cinderella awaited her savior in the form of Prince Charming, while Rene relied on his own biting wit and charm to keep him afloat, claiming: “I honestly don’t need much money. People love to buy me drinks. Hostesses love to feed me. Famous artists lavish me with expensive artworks, and heiresses do the same with jewels that I promptly lose.”

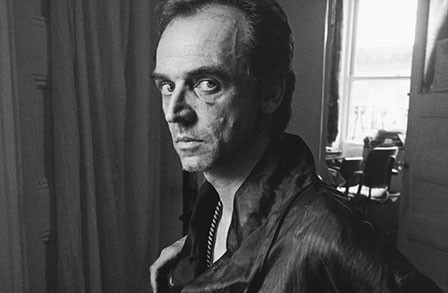

Rene was known for paying bills with paintings and skipping out on debts—had the artist acquired a glass slipper, the precious talisman would certainly have been sold or lost. A stark Nan Goldin portrait pictures Rene, in profile against a spray of cut flowers. He is smoking cocaine through a glass tube, to be discarded like the slipper once broken. He gazes down his aquiline nose, looking elegant even in his debauchery. He is a world away from the baby-faced blond, starlet Ricard in front of Andy Warhol’s camera. His swing from day to day between these poles of fame and debasement was as if by cursed enchantment, as Cinderella’s glittering carriage returned to its mundane form after midnight.

But Rene never doubted the power of transformation. In the final paragraph of Ricard’s seminal Basquiat essay “The Radiant Child”, he muses: “We are that radiant child and have spent our lives defending that little baby, constructing an adult around it to protect it from the unlisted signals of forces we have no control over. We are that little baby, the radiant child, and our name, what we are to become, is outside us and we must become “Judy Rifka” or “Jean-Michel” the way I became “Rene Ricard.”

This group of works dates from 1989-1990 as Rene Ricard prepared for Mal de Fin at the Petersburg Gallery, New York, in 1990, his very first one-man exhibition. Born Albert Napoleon Ricard, he moved to New York in the 1960s at the age of 18. With that relocation, Albert died, and Rene was born. Instantly adopted into Andy Warhol’s glittering orbit, Ricard thrived in the city, with its heady concentration of art, culture, and debauchery. In New York, Ricard found the milieu where he could shine.