At the beginning of the last century, a wave of disinterest and staleness had settled over Germany’s art scene. Artists from urban, cosmopolitan areas like Berlin, Munich and Dresden had become frustrated. They felt restricted by the strict bourgeois artistic ideals and state-sponsored traditional art education that was typical of the country’s culture and expectation at the time.

By 1905, a number of painters had begun to rebel. Instead of starchy, straightforward compositions, they loaded their canvases with bright, bold, often clashing shards of colour (reminiscent of Expressionism in general) and pared-down, jarringly distorted forms. The result of their work was raw, shocking and deeply emotive.

This new group of artists became known as German Expressionists. They were the forerunners of an experimental, multifaceted movement joined together in the belief that art should exude strong emotion whilst challenging the era’s social conservatism at the same time. A particular young group based in Dresden led by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner started things off. Their compatriots in Munich, spearheaded by Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, and Gabriele Münter, also came together under the name Der Blaue Reiter a few years later. Both factions created work which was deeply inspired by the subconscious and oozed with emotion. Indeed, these vibrant, distorted images that populated their paintings would go on to set the scene for mid-century abstraction later on.

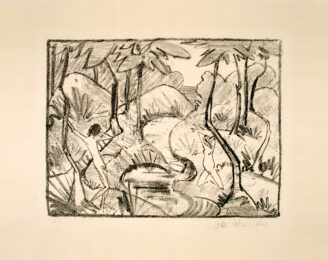

In the years between the First and Second World Wars, the concept of New Objectivity grew in strength. Urban artists such as Otto Dix, Max Pechstein, and Conrad Felixmüller honed in on a political discourse often related to the misery of World War I and its psychological toll on the citizens of Germany. Despondent, gaunt, ill-looking individuals fill these works. Indeed, many pieces were rendered in stark black and white prints whose shadowy palettes and simplified forms only served to emphasise their dark, mournful subject matter.