For 35 years Alistair Grant, the Royal College of Art and Printmaking were indivisible: 35 generations of artists learnt printmaking from him. Yet throughout his life Grant was as well known an artist as a teacher. He was a painter and a printmaker of considerable ability, and in his printmaking he was a great experimentalist. He fused media – litho with silk-screen, silk-screen with etching and often all three together.

Although born in London, he was half French. His mother was from Etaples on the coast of northern France. Grant went to school in Etaples and always retained the family home there. The region became the deeply rooted inspiration for much of his work throughout his life.

During the Second World War, he served as an air-crew wireless operator and was stationed in Egypt, where he met his first wife Phyllis Fricker. After the war, he was accepted into the Painting School of the Royal College of Art, graduating in 1950. Five years later he returned as Tutor in Printmaking. He became the Head of Department in 1970, and was made Professor in 1984.

Grant was the consummate head of department. His stated philosophy was that printmaking students should be encouraged not only to make prints but to paint and sculpt as well. (He himself exhibited widely on an international basis and his work is represented in major collections world-wide.) He insisted that all the teaching staff should be practising artists. He had a keenly developed political sensibility matched by an independence of mind and a toughness common to many of the staff who had been to art school following the experience of the war.

He loved the college, and enjoyed the tussles involved in promoting the interests of printmaking. When I was appointed to succeed him on his retirement from the college in 1990, I was the beneficiary of the best printmaking department in the country.

I had also been a student of Grant’s in the mid-Seventies. His students occupied a department bursting with equipment, expertise, confidence and energy. Grant was a tough taskmaster. He believed that strong criticism not only helped the work but engendered resilience – a commodity that would be much valued after graduation.

He was also an initiator. As a young tutor he had seen the potential of screenprinting for artists and introduced it into the department. He incorporated photo-imagery and encouraged wide artistic practice – making books, painting, sculpture, photography, drawing – all of which he believed made the artist bigger by informing the work more deeply.

Grant also had a strong entrepreneurial streak. In the Eighties he initiated the Royal College’s Printmaking Appeal Fund which published two of the most important print portfolios of the last few decades in order to raise funds for the printmaking students.

He brought an enormous professionalism and vision to these projects. Almost every important British artist of the second half of the century is represented. The initiative continues at the college and, in fact, Grant’s last print, Fete Champetre, a combination of litho and silk-screen in 18 colours, was made for The Royal College of Art Centenary portfolio, published in November 1996, and exhibited at the Victoria and Albert Museum as part of The Spirit of the Staircase, an exhibition which celebrated 100 years of print publishing at the Royal College of Art.

Alistair Grant was a large personality, a bon viveur. At the college he made sure that things in the Senior Common Room were as they should be – properly convivial. Through his French roots he was a knowledgeable chairman of the wine committee. His table at lunchtime was raucous. He was very likeable and very good company. He enjoyed telling his vast repertoire of jokes.

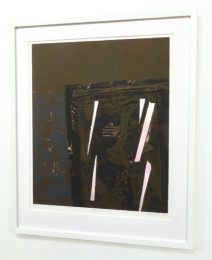

Over the years his work moved from figuration to abstraction. The colour, the forms and the hints of landscape became evocative of his native Pas de Calais. He was broadly skilled and was often commissioned to do illustrations. He was the hand behind the paintings in the Tony Hancock film The Rebel (1960). He made both sets of paintings for the film, “the good ones and the bad ones – whichever way around that might be”.