Details — Click to read

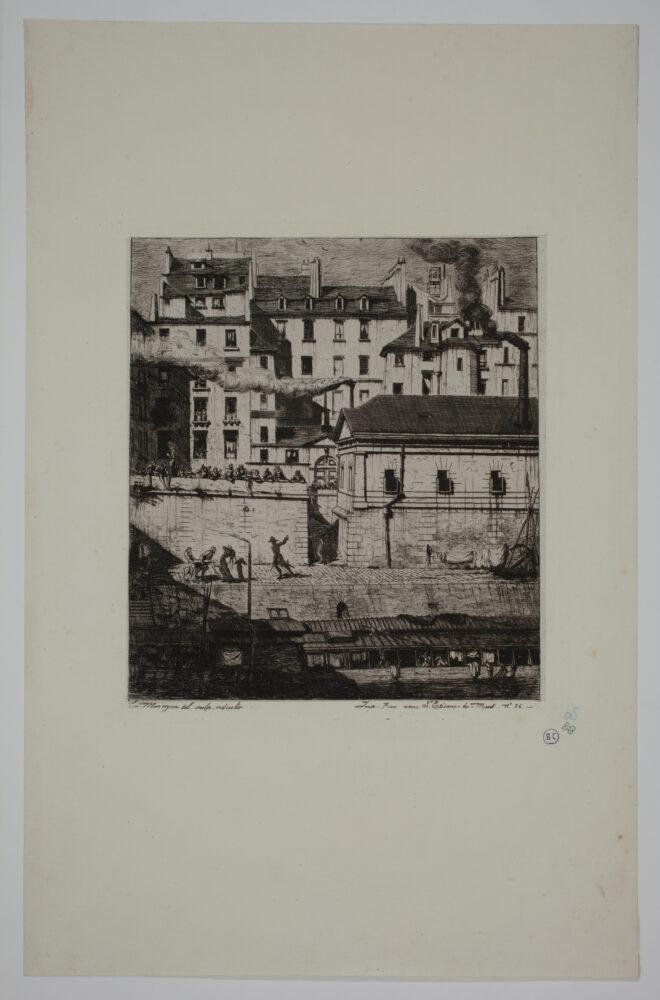

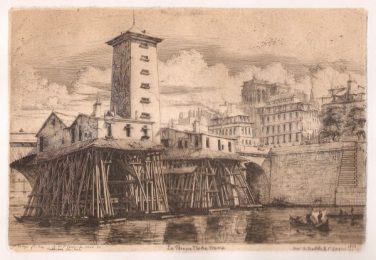

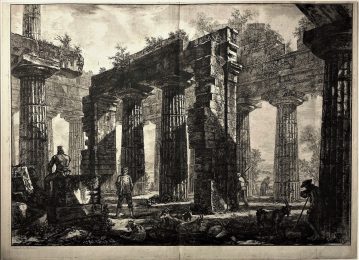

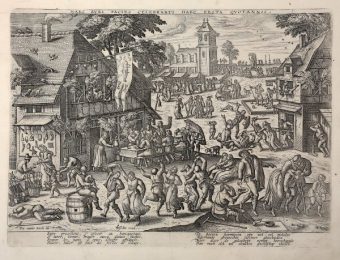

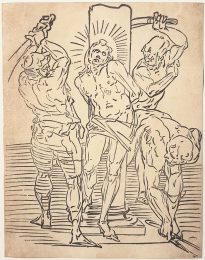

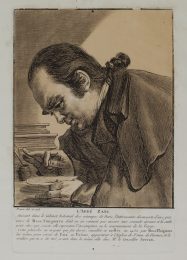

Etching and drypoint, 230 x 206 mm. Delteil 36, Schneiderman 42, 4th state (of 6).

Impression of the 4th state (of 6), with the inscriptions added in cursive in the bottom margin: C. Meryon del. sculp. mdcccliv. and Imp. Rue neuve St-Etienne-du-Mont. N°26.

Superb impression printed on chine appliqué on watermarked laid paper (HUDELIST). In excellent condition. A small inclusion in the paper (vegetal strand) on the roof of the Morgue and a thin crease in the laid paper under the chine appliqué (almost invisible). Two tiny foxmarks in the right margin. Full margins (sheet: 438 x 282 mm).

Provenance: A. Samana, a 20th-century Dutch collector who collected mainly 19th-century French prints: his collection mark printed in blue (Lugt 3454). Two other unidentified collector’s marks are printed next to it: a mark printed in purple, letters B and C in a circle (Lugt undescribed) and a mark printed in bluish green, arabesque (Lugt undescribed).

A “sinister, moving, extraordinary” work according to L. Delteil, La Morgue is the nineteenth plate out of twenty-two in the series Suite des Eaux fortes sur Paris [A Series of Etchings of Paris], published by Meryon between 1852 and 1854.

“In the eyes of a few connoisseurs,” Philippe Burty writes, “this piece is perhaps the most remarkable in all his œuvre. It would have been impossible to make this group of houses more moving; they are in reality very far from producing such a profound impression on one’s soul. The bizarre tiered arrangement of the roofs, the colliding angles, the blinding light that makes the contrast of darker masses all the more striking, the monument, taking, under the artist’s chisel, the vague aspect of an ancient tomb, all offer the mind an unspeakable enigma to which the figures give the sinister key; the crowd, huddled along the parapet, watches a tragedy unfold on the embankment: a corpse has just been fished out of the Seine; a small girl is sobbing; a distraught, frenzied woman falls backwards, choked by despair; the police sergeant orders the mariners to take to the Mortuary the poor wreck, a product of blackest poverty or debauchery.” (“L’œuvre de Charles Meryon”, Gazette des Beaux-Arts, 5, n° 15, 1863, p. 83, our translation).

Even though he etches the buildings and the embankment in minute detail, Meryon is acknowledged to be less worried about the faithfulness of representation than by the general impression he wants to produce. But this impression should not be the result of artifice, it must emanate directly from the contrasting lights and shadows on the façades of the houses, with their rows of dark windows, from the tiered lines of the roofs, with their chimneys shooting up into the sky like Gothic spires, and from the squat building of the Mortuary, with the crematorium chimneys coughing up a heavy smoke that struggles with rising in the air. The tragic scene of the body being fished out of the water under the gaze of onlookers leaning on the parapet reinforces the macabre feeling of the whole place. Burty justly writes: “The city, the street, the building, had been until then confined to playing the banal part of the background, but become here animated with the latent life of a collective being.” (Gazette des Beaux-Arts, 5, n° 14, 1863, p. 523, our translation). However this “latent life” is condemned to a sad destiny: the buildings would soon be demolished. Baudelaire was an admirer of the Eaux fortes sur Paris and offered to write “the philosophical reveries of a Parisian flâneur” to accompany the etchings. But Meryon was not a fan of “poetical meditations in prose” and replied curtly that it was important to stick to a strict description of the prints and the places they represented:

“One has to write: on the right, this can be seen; on the left, that can be seen. One has to research and take notes from old books. One has to say: this building originally had twelve windows, but the artist only represented six; and, finally, one has to go up to the Hôtel de Ville to ask about the exact year of the demolitions.” Baudelaire added: “M. Meryon talks and talks, gazing up to the ceiling, listening not a whit to one’s observations.” (Letter to M. Poulet-Malassis, 16 February 1860, quoted in Le Peintre-graveur illustré, vol. 2, Charles Meryon, by L. Delteil).

The mortuary and the buildings sketched by Meryon were situated at the beginning of the Quai du Marché neuf, where the Préfecture de Paris now stands. At the same time that he added the title in the 5th state, Meryon engraved on a façade to the left: HOTEL DES TROIS BALANCES MEUBLE and on another one to the right: SABRA – DENTISTE DU PEUPLE. The Hôtel des trois balances did indeed stand at number 6, Quai du Marché neuf. As for Sabra, “the people’s dentist”, he owed his reputation to his affordable prices, and he moved to the other side of the boulevard, at the corner of Quai des Orfèvres, in the 1860s after the buildings of the Quai du Marché neuf were demolished.

Meryon modified the copperplate for The Mortuary in 1863. The 7th and last state bears an additional inscription: IMAGERIE RELIGIEUSE EXPORTATION [Religious images for export]. This is probably the publishing house of Charles-Eugène Glémarec, specialising in popular images engraved in wood, which was established in 1847 at number 30, Quai du Marché neuf. A photograph of the mortuary and of the houses on the Quai, taken by Henri Le Secq in 1855, testifies to the sheer number of inscriptions covering the façades of the buildings at the time.

References: Philippe Burty, « L’œuvre de Charles Meryon », in Gazette des Beaux-Arts, 5, n°14 et n°15, 1863, pp. 76-88; Loÿs Delteil, Le Peintre-graveur illustré, vol. 2, Charles Meryon, 1907; C. Geoffroy, Charles Meryon, H. Floury, 1926; Richard S. Schneiderman, The Catalogue raisonné of the Prints of Charles Meryon, Garton & Co., 1990; Gallica: Avril Frères, Plan d’expropriation pour la construction de la préfecture de police et du marché aux fleurs.

![La Morgue [The Mortuary] by Charles Meryon](https://www.printed-editions.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/meryon_morgue-3-scaled.jpg)