Details — Click to read

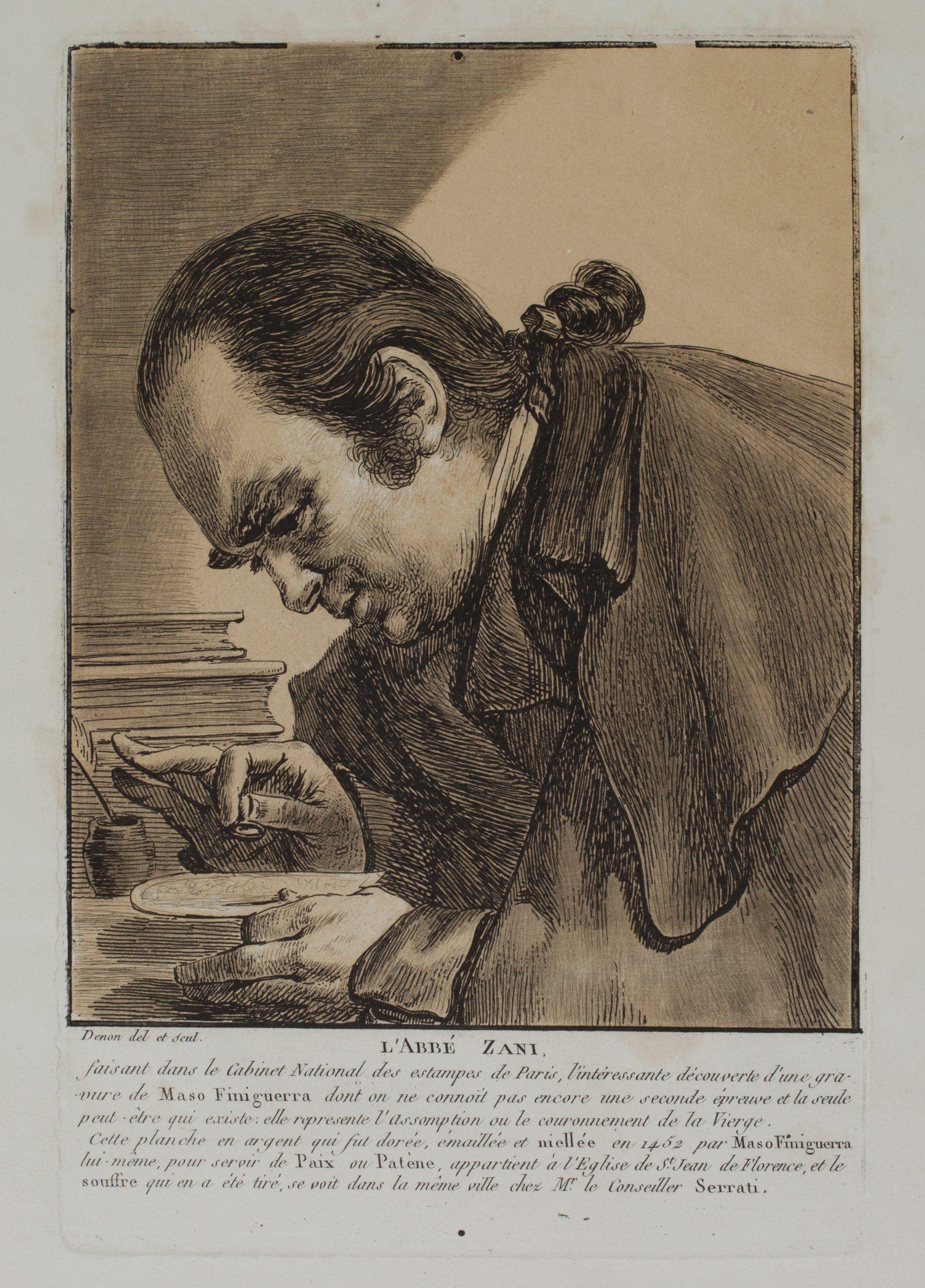

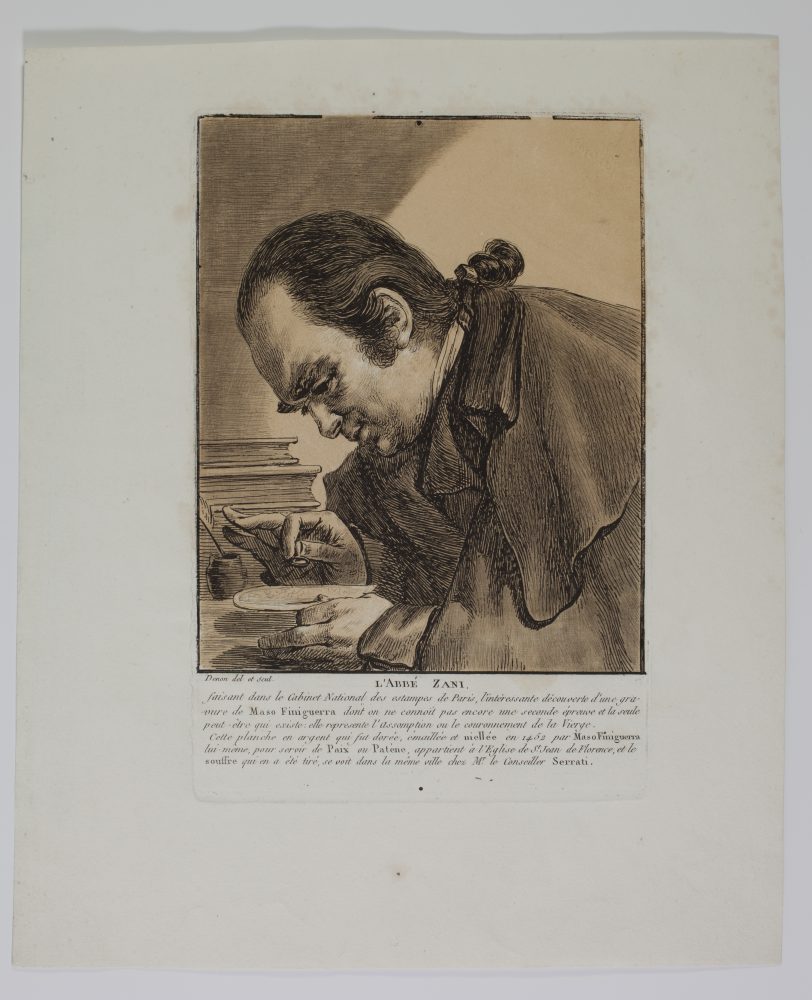

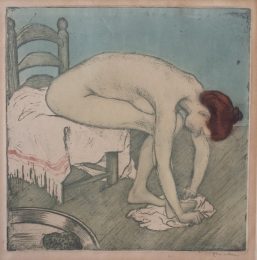

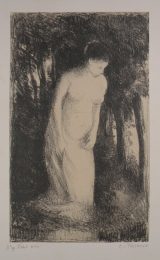

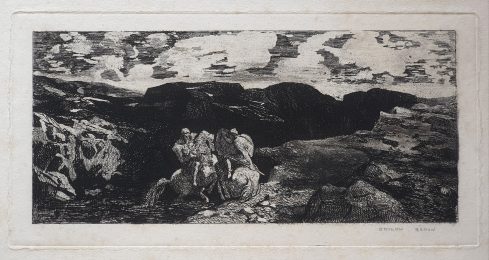

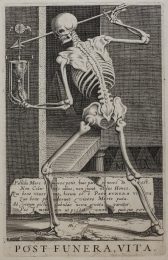

Etching, drypoint and lavis manner, 206 x 135 mm. IFF 341, 3rd state (of 3); De la Fizelière 209, The Illustrated Bartsch, vol. 121, no. 191

Impression of the 3rd state (of 3), with the new works in drypoint, the surface tone from an additional plate, and the letter engraved bottom.

Very fine impression printed with registration marks on wove paper. In very good condition. A few light foxmarks in the margins. Good margins (sheet: 276 x 230 mm).

Vivant Denon expounds the subject of the etching in the long letter engraved underneath the portrait: “The ABBÉ ZANI, making, in the Cabinet National des Estampes at Paris, the interesting discovery of an engraving by Maso Finiguerra, of which no second proof is known as yet, and which is possibly the only one in existence: it represents the Assumption or the Coronation of the Virgin. This silver plate, which was gilded, enamelled and nielloed in 1452 by Maso Finiguerra himself, to serve as a Pax or Paten, belongs to the Church of St. John of Florence, and the sulphur that was made on it, can be seen in the same city at the house of Councillor Serrati.”

In 1797, the abbé Zani discovered a niello print representing the Coronation of the Virgin in one of the volumes of Old Master prints in the collection of Abbé de Marolles, which forms the core of the collection of prints in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. This impression, the only one preserved today, results either from the printing on paper of the gilded and nielloed silver plate created in 1452 for the church of San Giovanni in Florence, currently in the Bargello museum (inv.33 O.R.), or from the printing of a sulphur cast made on the silver plate. Only two sulphur casts are known: one is in the British Museum, the other in the Edmond de Rothschild collection in the Département des Arts Graphiques at the Louvre.

The discovery of this unique impression by the abbé Zani was important: it was indeed the oldest preserved Italian “engraving”. As Gisèle Lambert explains: “in Italy, the origin of the first engravings can be traced back to goldsmiths’ works called niello plates. Impressions were printed on paper from gold or silver plates that had been engraved in order to be nielloed (or sometimes from a sulphur cast used as an intermediate). This goldsmithing technique was the origin of the development of engraving in the country, giving it a distinct originality.” The printing of a proof on paper “allowed the goldsmith to control his work – since the niello operation did not allow any retouching -, and to keep a record of his work, and perhaps also to constitute a book of models. It was not intended to be distributed, which explains the rarity of the preserved copies.” (Gisèle Lambert, “Nielles“, §1 and 3, in Les Premières Gravures Italiennes, translated by us). At the time of the abbé Zani’s discovery, Maso Finiguerra’s niello on paper was even considered to be an impression of the very first datable engraving, making the discovery even more sensational.

Jean Duchesne aîné, who was then a young assistant at the Cabinet des Estampes of the Bibliothèque nationale, described the enthusiasm of the abbé Zani when he communicated his discovery to the curators of the Cabinet in 1798: “It would be difficult to paint the joy of the esteemed Abbé Zani, at the moment when, having acquired the certainty of his discovery, he hastened to inform us. This excellent man was so deaf that he could hardly hear the compliments that were made to him on the importance of the piece, which he had recognized as an impression drawn by Maso Finiguerra, after a plate engraved by him. His French being very poor, he expressed himself with great difficulty, and then, seeking to make himself better understood, he switched to Italian; then, to explain himself even better, he used Latin phrases that his pronunciation made it difficult to understand, and technical expressions, whose accuracy we often could not recognise; using unceasingly the words niello, niellare, niellatore, whose meaning was not known to us; the whole intermingled with joyful exclamations, of which he gave an account in his work, with wonderful naivety and bonhomie; one would however be quite at fault if one were to consider these the forgivable ramblings of an old man, prone to mere rhapsodic effusions in his work. The agitation that seized Abbé Zani seemed all the more singular, since for the last six months he had been coming to sit in the same place every day, and it was plain to see that his infirmity made him quite similar to a stone post, and prevented him from taking part in anything that happened around him. I was very young at that time, and not able to attach to this interesting discovery as much importance as our learned amateur; I will never forget however the singular scene presented by the state of effusive enthusiasm of our esteemed Abbé Zani; it made such a strong impression on me, that after more than twenty-five years, it is still perfectly vivid in my mind.” (Essai sur les nielles, 1826, pp. 55-56, translated by us).

The endearing portrait of the abbé Pietro Zani etched by Dominique Vivant Denon is a vivid testimony of this discovery and the impression it made on the artist. Pietro Zani wrote: “I did not delay a moment in declaring my discovery to M. Joly […] curator of the Cabinet (of France), to his employees and to several of his friends, among whom was the famous M. Denon, who wanted to engrave my portrait at once, at the very moment when he had seen me, magnifying glass in hand, examining this print”. (Materiali per servire alla storia dell’origine e de progressi dell’incisione in rame e in legno, e sposizione dell’interessante scoperta d’una stampa originale del celebre Maso Finiguerra, quote translated in French by Georges Duplessis in Histoire de la Gravure, 1880, p. 31, translated by us).

Although it has since lost its status as the very first engraving, Maso Finiguerra’s niello print remains an important milestone in the history of engraving. The portrait engraved by Vivant-Denon testifies in turn, through the etching itself, to the pleasure and enthusiasm of historians and amateurs for precious prints, whose qualities they are delighted to examine, and whose artistic and historical importance they justly value.

References: Albert de la Fizelière, L’œuvre originale de Vivant Denon, 1873; Gisèle Lambert, Les premières gravures italiennes : Quattrocento-début du cinquecento. Inventaire de la collection du département des Estampes et de la Photographie. New online edition; Jean Duchesne, Essai sur les nielles, 1826; Georges Duplessis, Histoire de la Gravure, 1880.