1863-1944

Before Munch’s well-known breakdown in 1909, the great Norwegian artist threw himself into printmaking with a zeal rarely seen among history’s greatest artists: not only as a master printmaker in the tradition of Rembrandt, Goya, and Cassatt (among others), but as an innovator of striking originality whose influence on subsequent printmakers still reverberates, primarily but not exclusively in woodcut.

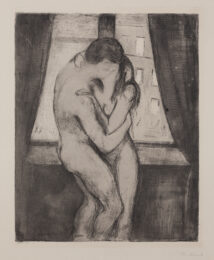

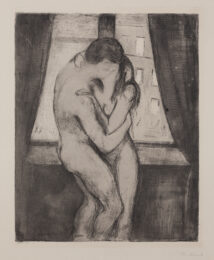

Edvard Munch prints began with drypoint in 1894, the first media he would master, as he seemed to have a natural aptitude for all accessible printmaking techniques. A few weeks later, he began working with etching and lithography. He could draw on-site at the artist gatherings at Zum Schwarzen Ferkal with a needle in his pocket and copper, which was perhaps the easiest material to work on (The Black Piglet, the famous watering hole to the Berlin Bohemia). Considering its ease of use and lack of chemicals, drypoint also made sense as an introduction to printmaking. The established themes from Munch’s The Frieze of Life series, which comprised some of his most well-known early paintings, such as The Scream, Jealousy, and Puberty, among others, were, nonetheless, his primary emphasis. When describing the drypoint version of Night in St. Cloud, his patron Julius Meier-Graefe (the most well-known German art historian of the time, the author of Dostoyevsky’s biography, and the one who first encouraged Munch to try his hand at printmaking) wrote: “Like all decent engravings,” (in this case drypoints/etchings), “these prints appear colourful, without any colour. If one cannot detect this impact, one must be blind or very well-educated. All of them have the same theme and are extraordinarily talented paintings, which one does not miss here.

In order to avoid having to press down on the copper with the needle in order to create a burr, sketching over etching ground allowed for a much greater and easier fluidity of line, which is why Edvard Munch prints turned to etching. The drypoint’s burr also quickly degraded after several passes through the press. Quantity was crucial to the artist who was business-minded. In keeping with his rather unpolished painting style, open bite, which involves allowing huge open regions of copper to be etched and produces an asymmetrical tonal effect in the print, captivated Munch as well. There are hundreds of his etchings, but perhaps we should stop talking about them now that we’ve briefly covered Munch’s mastery of intaglio printing with a few examples, keeping in mind that he never completely abandoned this medium and learned it for the most part on his own (as he did all techniques save for lithography, which involves considerable know-how and a good deal of chemistry).

More or less concurrently with his etchings, Munch started producing lithographs, and he seemed more drawn to the medium for its capacity for reproduction than for its expressive qualities. Printing etchings required extra work because the plates needed to be prepared (e.g. several trips into the acid bath). As we have indicated, drypoints quickly wore off, affecting the image. Lithography allowed for nearly unlimited copies and satisfied Munch’s passion of drawing in the purest and most traditional sense of printmaking (the technique of drawing on stone with lithographic crayon and ink-like touche was as easy as drawing on paper, and is in general a more sensual experience). Munch finally had a method for disseminating his drawings widely. In fact, two years after Munch’s passing, Paul Gaugin’s son Pola Gaugin published Gerafikeren: Edvard Munch, the first book on his printed works.

In Berlin, where the printing technique was at the time becoming more and more well-liked, Munch started producing lithographs. He also spent some time in Paris at the Atelier Clot, where he produced an edition of Angst for a portfolio for numerous people, including Eduard Vollard, who at the time was France’s most well-known print champion and publisher. Although Munch would continue to work in lithography for a number of years, the burden of the extraordinarily heavy Bavarian limestone required for the technique was too much for him, and a few years later he switched to woodcut, which would end up being his primary, but not only, print medium for the rest of his life (both for its simplicity and expressive qualities).

It is impossible to emphasise how inventive Munch was in the woodcut medium. Few artists have dared to try his approaches because of how creatively and actively he handled a classic Germanic material (not, I suspect, because of the difficulty involved but because their sheer originality, like his painting, defies imitation).

Using two blocks (one for the main image and one for the background) that were both carefully cut to puzzle-like shapes, Munch invented a method in which he would use a jigsaw to cut his blocks into individual areas. These shapes were then inked in multiple colours before being reassembled and printed in one pass. In addition, he and Gaugin were the first artists to use the wood’s grain for expressive reasons (Gaugin was working independently from Munch).

Early in the 20th century, the burgeoning German Expressionist group Die Bruke had great success with these woodcuts. It was left to the great Karl Schmitt-Rottluff to approach Munch in 1906 with an invitation to join the group as its “Spiritual Father,” a position the eternal outsider and loner denied. The group comprised Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Erich Heckel, and Emil Nolde among its luminaries.

The brutality, carving, and gauging of the wood speak to Munch’s frequently heavy-handed use of the brush when painting: piling strokes one upon the other which then exist alongside vast areas of wash with canvas showing through. Although Munch continued to work in other print media until his death, the surface of wood is perfectly suited to his imagery and working mentality. In a similar manner, the wood can have a wide variety of marks that contrast with broad expanses of flowing, grainy backdrop while producing a frenetic concentration in select locations.

Munch could not have avoided seeing examples of Ukiyoe (“Floating World”) prints in Paris, which had made their way to Europe as packing for the porcelain craze after Japan’s reopening to the West in the 1850s. This is where a digression on the Japanese influence on European printmaking should be addressed. In a branch of Impressionism known as Japanism, Impressionists like Cassatt, Manet, and Toulouse Lautrec were absorbing the handling of huge colourful areas, pattern, and detail in these prints.

As usual, Munch pushed this to even more avant-garde techniques with his distinctive jigsaw technique and undulating grains. It should be emphasised that the Japanese woodcut printing method differs from Munch’s usage of the Western etching press (sorry for the Wikipedia link, but it is brief and many readers are already aware with moku hanga). He preferred the coarse grains of spruce, pine, plywood, and mahogany over the Japanese cherry wood, which was of a much softer sort. These were also simpler to cut since cherry wood is very durable and more suited to the intricate Japanese designs.

In order to demonstrate how persistent Munch was in his pursuit of the woodcut, as well as how their directness provides an emotional intensity and immediacy that never left the artist, I provide this final example from 1930 of the Norwegian folk heroine Birgitte.

It is impossible to overstate Munch’s influence on modern printmaking, but it is important to note that, in contrast to many of his contemporaries and those of our day, Munch showed little interest in creating editions, with the exception of officially produced portfolios by publishers (in which case he had printers at his disposal, and viewed the experience as a business venture as much as a creative one). The endless diversity of inking, assemblage, and materials, as well as the experimental character of printmaking, drew him more. It’s significant to notice that he rarely produced the same print again in woodcut.

It is also noteworthy that Edvard Munch prints were created primarily for financial reasons because he could sell them for far less than his paintings and regarded the endeavour as a way to boost his (already impressive) income.

Edvard Munch prints are thought to have numbered 748 registered print works throughout his lifetime, each of which had between 20,000 and 25,000 impressions. This appears to make him the most prolific printmaker in history, if not the most inventive—surpassing even the enormous Picasso.

Read the Blog: Edvard Munch Prints And His Paris Sojourn.