Details — Click to read

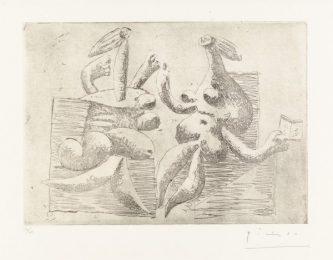

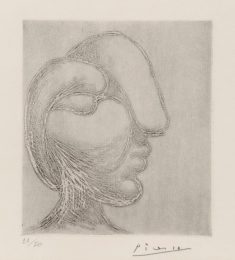

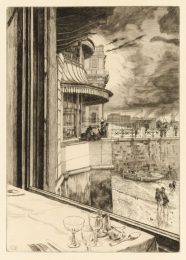

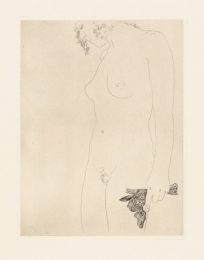

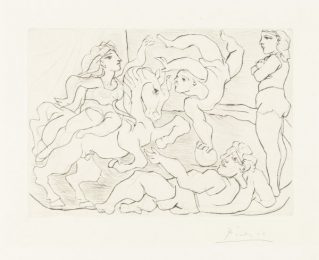

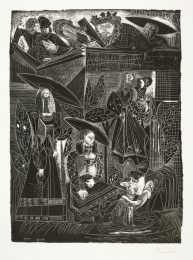

Original etching and drypoint printed in black ink on laid paper.

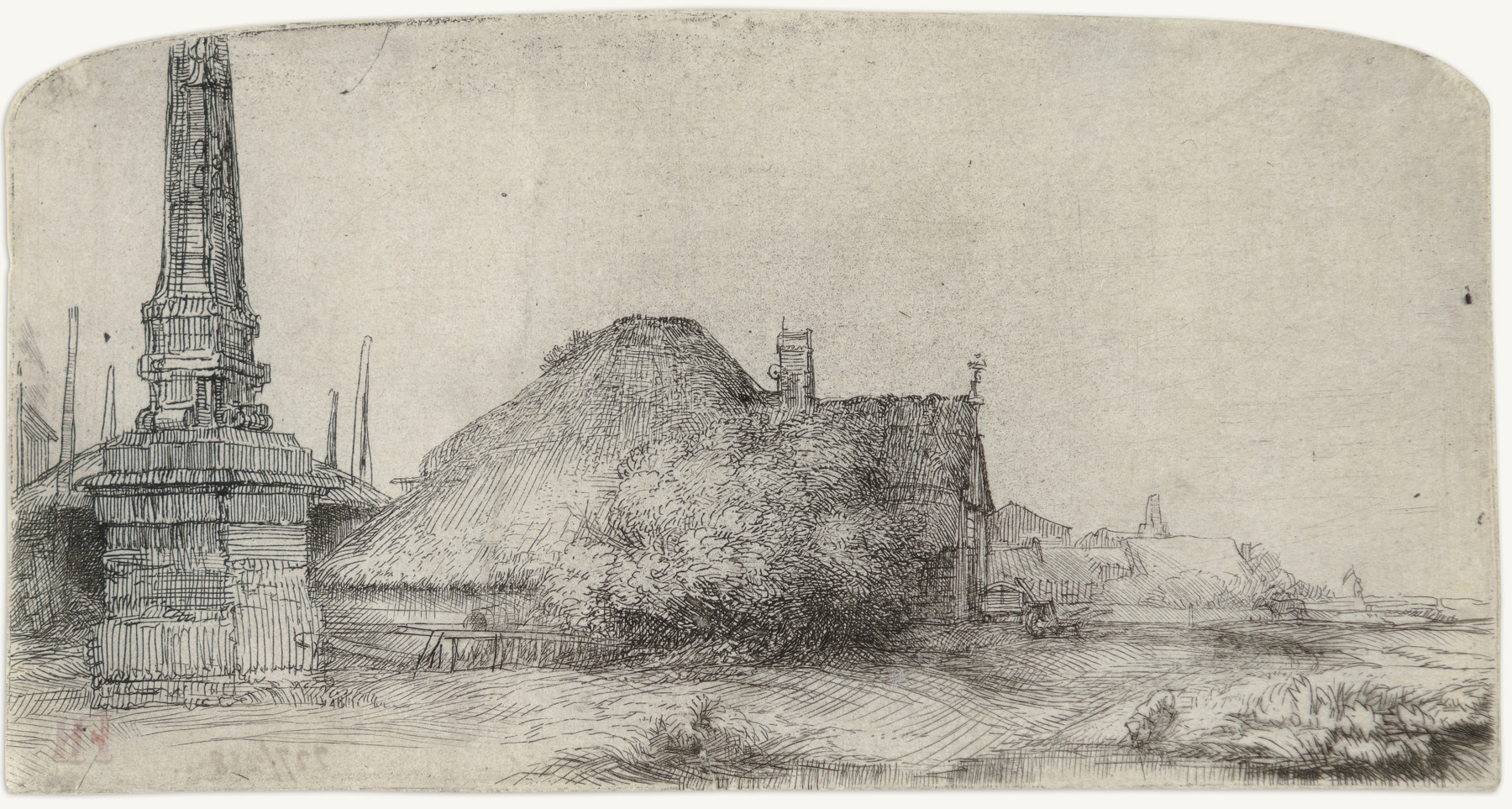

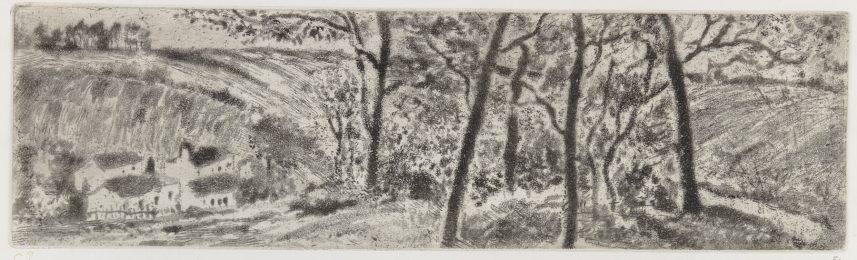

A strong and dark 17th century/lifetime impression of Bartsch, Usticke and New Hollstein’s second and final state of this rare etching (characterized by G.W. Nowell-Usticke in his 1967 catalogue Rembrandt’s Etchings: States and Values as “a scarce arched landscape,” and assigned his scarcity rating of “R” [75-125 impressions extant in that year]), printed after the addition of shading to the cottage and paling behind the wheelbarrow at the right, showing touches of burr along the lower edge

Catalog: Bartsch 227 ii/ii; Hind 243; Biorklund-Barnard 50-3; Usticke 227 ii/ii; New Hollstein 249 ii/ii.

3 5/16 x 6 3/8 inches

Trimmed down to the platemark all around, otherwise in excellent condition.

Provenance: Nathaniel Smith (British, c. 1740-1809), a well-known London sculptor and Old Master print-dealer and collector with fifty years in business, bearing his paraph (Lugt 1988) by hand in ink verso; also bearing an unidentified collection stamp (the letters “FH” in red ink) verso.

Collections in which impressions of this state of this etching can be found: Rijksprentenkabinet, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam; Kupferstichkabinett der Staatlichen Museen, Berlin-Dahlem; Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge; Städelsches Kunst institut, Frankfurt-on-Main; Teylers Stichting, Haarlem; Ermitage Museum, Leningrad; The British Museum, London; Pierpont Morgan Library, New York; Ashmolean Museum, Oxford; Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris; Duthuit Collection, Petit Palais, Paris; Collection Edmond de Rothschild, Musée du Louvre, Paris; Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna.

During Rembrandt’s day in the hamlet of Spieringshorn, where between ten and fifteen cottages lay spread along the foot of the dyke, the most remarkable feature one would have encountered were two hardstone obelisks, that functioned as boundary stones. They had been placed there by the Amsterdam city council to mark the official boundary. The older obelisk closer to the city dated from 1559; after the extension of 1610-14 a new boundary stone was erected in 1624, further away from the city.

The well-know etching by Rembrandt traditionally known as “The Obelisk” is based on drawings he made of this second boundary stone in its setting. In the center of the etching we see a thatched cottage of the langhuisstolp type. We just glimpse the front wall of the fore-house, with its door and window above it, and the extended king-post. The brick chimney, marking the division between the dwelling section and the barn, has a cap construction presumably against the rain and probably also has a starling pot. The construction of the barn section of the cottage isn’t completely clear. At the back te roof os somewhat raised to accommodate a doorway that carts can drive through; above this is a perch for pigeons. On this side the roof slopes down until it is close to the ground. The front of the building is presumably built on an artificial mound, for tem base of the side wall is lower than that of the front wall.

A wheelbarrow stands in front of the cottage with a somewhat unclear construction behind it, possibly a cart. Against the side wall, partly protected by the low-hanging thatch, is a rack on which a milk pail or jug is drying. Behind the cottage, half hidden by the boundary stone, is a low haystack, suggesting that much of it has already been used and the winter months are over.

The position of the cottage appears rather curious. In the foreground is the bank of a pool or ditch, with a dog drinking from the water. The indistinct track of cart wheels runs from them water and in front of the cottage towards some dwellings grouped around what looks like a church tower. Halfway along, a cow is standing in the grass and further away is a man with a scythe.

The obelisk commands at least as much attention as the cottage. It is a solid hardstone pillar standing on a tall brick pedestal. On te upper side fo the base are three hardstone plates, the central one serving as a drip, that is, a projection at the edge of the cornice designed to throw water clear. Resting on these plates is a block consisting of two sections, decorated with scrolls, on which stood the actual obelisk. In the upper half of the block there was a text inscribed in Latin or Dutch stating that this point marked a judicial boundary line. About halfway up the obelisk were two oval shields which appear to be repeated on the left side; these oval apparently contained the Amsterdam city arms surmounted by the emperor’s crown.

It is significant that Rembrandt first made an etching of a far shorter obelisk, the tip of which, crowned with a ball, reached to the edge of the paper. Apparently, on consideration he made the obelisk taller and thicker, thereby adding considerably to the strength and force of the etching’s composition. Also interesting is the fact that Rembrandt presents the haystack in a kind of symmetrical balance to the obelisk so that the rick and its four poles appears to become part of the stone needle.