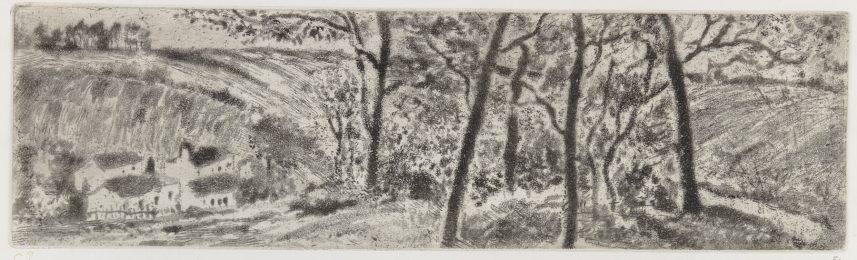

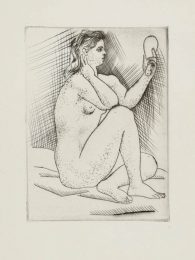

Details — Click to read

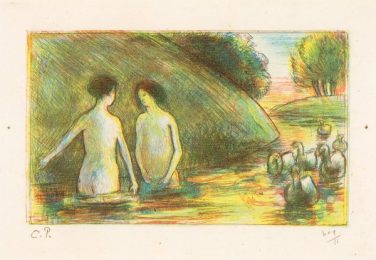

Literature regarding this artwork: Krystyna Matyjaszkiewicz, James Tissot, Barbican Art Gallery & Phaidon Press, London, 1984, no. 113, p. 121 (ill.);

Willard E. Misfeldt, J.J. Tissot: Prints from the Gotlieb Collection, Art Services International, Alexandria, Virginia, 1991, no. 29b, p. 87 (ill.);

Nancy Rose Marshall/Malcolm Warner, James Tissot: Victorian Life/Modern Love, Yale University Press, New Haven & London, 1999, no. 22, p. 69 (ill.)

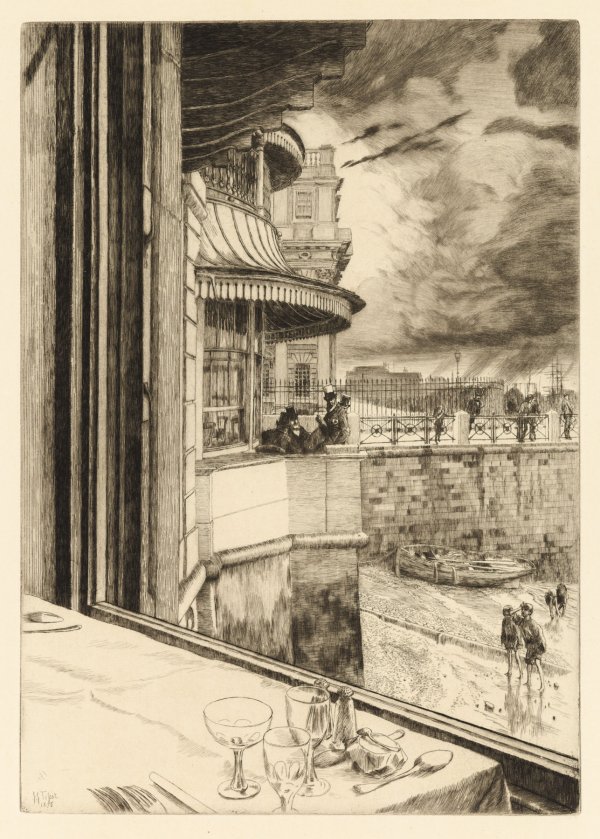

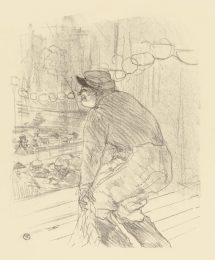

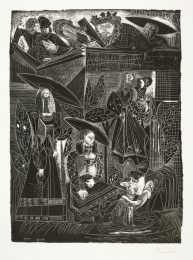

The tavern is shown from the vantage point of a guest sitting at a table in the dining room, the luxury is signaled by a place setting of three glasses, three spoons, and two forks, all as yet untouched. Designed by Joseph Kay in 1837, the Trafalgar was famous for its “whitebait suppers,” expensive fish meals unique to London. It also had strong naval associations; its balconies were copies of the stern gallery of H.M.S. Victory, Nelson’s ship at the battle of Trafalgar. Significantly, this was also the venue for an annual political event, the Parliamentary fish dinner, a famous occasion for members of Parliament to indulge themselves in food and drink. The tradition had originated in the eighteenth century, and though temporarily discontinued in 1868, was revived under Disraeli in 1874.

In Tissot’s etching, the men on the balcony occupy a recognized position of power, a site of government authority, in contrast with the ragged boys literally and figuratively below them. Their top hats, black coats, and casual ease bear witness to their privileged place in society. The boys, on the other hand, are hatless and shoeless, their scrawny legs suggesting poverty and vulnerability. Creeping up the wall of the tavern is a dark stain,which threatens the smooth, blank whiteness of its stone façade; literally intended as algae, it serves as a metaphor for the living conditions of the children, who are probably “mudlarks,” familiar London types described by urban ethnographer Henry Mayhew in his London Labour and the London Poor. Scavenging the shores at low tide for coal, iron, and copper nails from barges and shipbuilding concerns, these gleaners of society’s refuse occupied the bottom of the social hierarchy. A series of barriers, including the balcony wall, the cast-iron fence of the terrace, and the high enclosure around the Greenwich Hospital, underscore the divisions between the haves and the have-nots.