Details — Click to read

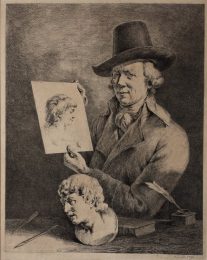

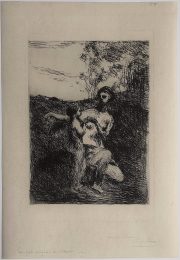

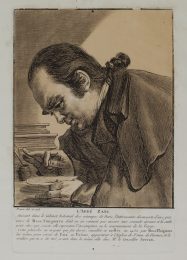

[Bust of a Young Woman, after Boucher]

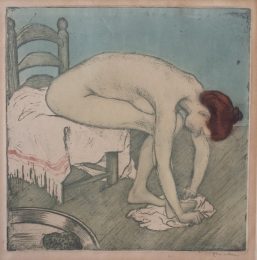

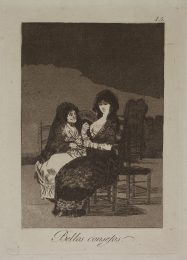

Trois crayons manner, printed in red, black and white inks on blue paper, 311 x 230 mm. Hérold 9, 1st state (of 4).

Very scarce impression of the first state (of 4), before the letter was changed and before several borderlines were added, as well as two more plates, one for blue ink and one for yellow ink.

Superb impression with very fresh colors, printed on blue laid paper (the color of the sheet slightly faded).

In excellent condition. Small margins all around the platemark (sheet: about 325 x 245 mm). The sheet is pasted by the edges on a sheet of thin wove paper and a mat is pasted by a few dots of glue on the backing sheet.

The rather large, detailed text engraved underneath the subject only appears on impressions from the first state. It states that this work is the first to have been engraved by Bonnet in the trois crayons manner, that is, in red, black and white: “First print in the trois crayons manner after a drawing by M. Boucher / first painter to the King. Engraved by Louis Bonnet, who alone knows the / secret to printing whites from the Cabinet of M. de la Garégade, / Treasurer General to the Navy. / Paris, at the Widow Chéreau’s rue St. Jacques at the Two Golden Pillars. / and at Bonnet’s rue Gallante, find the carriage door between a candelabra and a dairy, opposite the rue du Fouar.”

These mentions also figure in the announcement published in the 18 May 1767 issue of L’Avant-Coureur (a magazine advertising news in science and the arts), concerning the publication by Bonnet of a “Bust engraved with the trois crayons method”. Louis-Marin Bonnet had just returned from a two-year stay in Russia; this might mean, according to Jacques Hérold, that this print could have been engraved before 1765. The advertisement in L’Avant-Coureur tells us more about the circumstances in which the print was published: “M. Bonnet, engraver in the chalk manner, recently published a Bust engraved with the trois crayons method, after a drawing by M. Boucher. The execution of such prints was fraught with difficulties, the most important of which were, to adjust the colours between the different plates, and the need to use a white ink, which color could be permanent. Different trials released by this Artist in recent years have proved to Connoisseurs of the art of Drawing that he was able to overcome these obstacles: eager to further explore this happy discovery, he engraved a Bust in the trois crayons method, which work he is only now presenting to the public, having received the approval of several famous established Artists. This print will soon be followed by another Bust in the pastel manner. This Engraving, or rather, this Drawing, can be bought in Paris at the Widow Chereau, rue S. Jacques; and at M. Bonnet’s, rue Galande, opposite the rue du Fouare.” (our translation)

Growing interest for drawing in the 18th century, especially for sketches in two or three colours of chalks and pastels, pushed printmakers to look for techniques that could imitate the texture and feel of chalks, as explained by the Encyclopédie in 1767, in the entry “Engraving in the chalk manner”: “The aim of this manner of engraving is to produce an illusion, to the point that at first glance the real connoisseur will not be able to tell the difference between the original sketch and the engraved print that is an imitation of it” (Recueil de planches, volume IV, plate VIII, our translation). For printmakers trying to produce a perfect imitation of drawings and sketches, what was at stake had pedagogical, artistic and commercial implications: prints in the chalk manner made it easier to teach draughtsmanship technique to art students, who could copy the best artists of the time; they also allowed for wider circulation and knowledge of artistic works in the public ; lastly, and importantly, they created a new market that targeted people who appreciated sketches as well as print collectors.

Mostly from 1757 onwards, the engraver and printer Jean-Charles François developed the technique of engraving in the chalk manner: this imitated the quality of simple sanguine sketches, with the use of a roulette. That tool had until then only been used to add a few details to an engraving. Jean-Charles François was followed by Gilles Demarteau, Alexis Magny and Thérèse-Éléonore Lingée.

Louis-Marin Bonnet wanted to perfect the technique. Margaret Morgan Grasselli notes that “Bonnet was not content simply to turn out print after print in the standard chalk-manner technique. Instead, this inspired and determined innovator expanded the possibilities of the medium in a variety of directions. One of his first innovations was the formulation in about 1763 of a white printer’s ink that could effectively imitate the appearance of white chalk and white gouache, but would not turn yellow or black over time. This new ink revolutionized chalk-manner engraving and greatly expanded the types of drawings that could be reproduced in prints.” (Colorful impressions, p. 54).

Bonnet then decided to attempt engraving in the two or three crayons manner, that is, to imitate sketches in black chalk or in sanguine with white chalk details, or sketches that combined all three colours. This Bust after Boucher is his first engraving in the trois crayons manner. In a fascinating chapter, Ink and Inspiration – The Craft of Color Printing, Judith C. Walsh examined this print and analysed Bonnet’s work: “The red and black were likely printed from one plate each, but the white required two plates. The smudged white highlighting on the flesh of the sitter was printed in a small dot pattern from a deeply gouged plate, which put excess white ink on the sheet. The still wet white was evidently quickly overprinted, causing it to squash and spread slightly in a re-creation of smudged white chalk. The plate bearing the long, thick, white lines that describe folds in the bodice was charged with the same white ink, but as it was the last bit printed, the ink of the impasto “chalk” line dried proud of the sheet.” (Colorful impressions, p. 27).

Having mastered each separate step of this painstaking work, Bonnet was able to create subtle trompe-l’œil effects. Margaret Morgan Grasselli notes that “since Bonnet never shared the secret of his white ink with anyone, he was the only chalk-manner printmaker to use it. He quickly capitalized on his monopoly, making a specialty of multicolored prints.” (Colorful impressions, p. 54).

The following issue of L’Avant-Coureur, dated 25 May 1767, announced the publication of prints by Demarteau described as “Busts of women” engraved “with several colors in the crayons manner” in which the “thick and oily qualities of chalk are faithfully reflected.” But Sophie Raux points out that “contrary to Bonnet, Demarteau and François were never able to discover the secret of the white ink and were forced to use the white of the paper as a workaround to artificially suggest white chalk highlights” and that “they were never able to reproduce the stunning textures that Bonnet achieved by overprinting with a plate inked in white.” (Quand la gravure fait illusion, p. 60, our translation).

The second state of Bust of a Young Woman after Boucher was advertised less than five months later, in the 12 October 1767 issue of L’Avant-Coureur, under the title “Bust engraved in the pastel-manner, after M. Boucher” (our translation). Whereas impressions from the first state had four lines of text, only one line is left in the second state, and five square strokes have been added. Two new plates were used: one to add a blue tinge to the subject and to the mat, and the other to bring shades of yellow onto the garment and mat. This is Bonnet’s first engraving in the pastel manner. In the third state, an impression of which is in the Louvre in the Edmond de Rothschild collection, Bonnet returns to the trois crayons method, which is easier to implement. The fourth state only involves two plates in black and red on white paper.

Impressions from the first state are very rare. The impression examined by Judith C. Walsh and exhibited in Washington for Colorful Impressions: The Printmaking Revolution in Eighteenth-Century France is in the National Gallery of Art.

References: Jacques Herold: Louis-Marin Bonnet (1735-1793) : Catalogue de l’œuvre gravé, 1935; Colorful Impressions: The Printmaking Revolution in Eighteenth-Century France, 2003; Quand la gravure fait illusion : Autour de Watteau et de Boucher, le dessin gravé au XVIIIe siècle, 2006.