Anni Albers Prints & Textiles

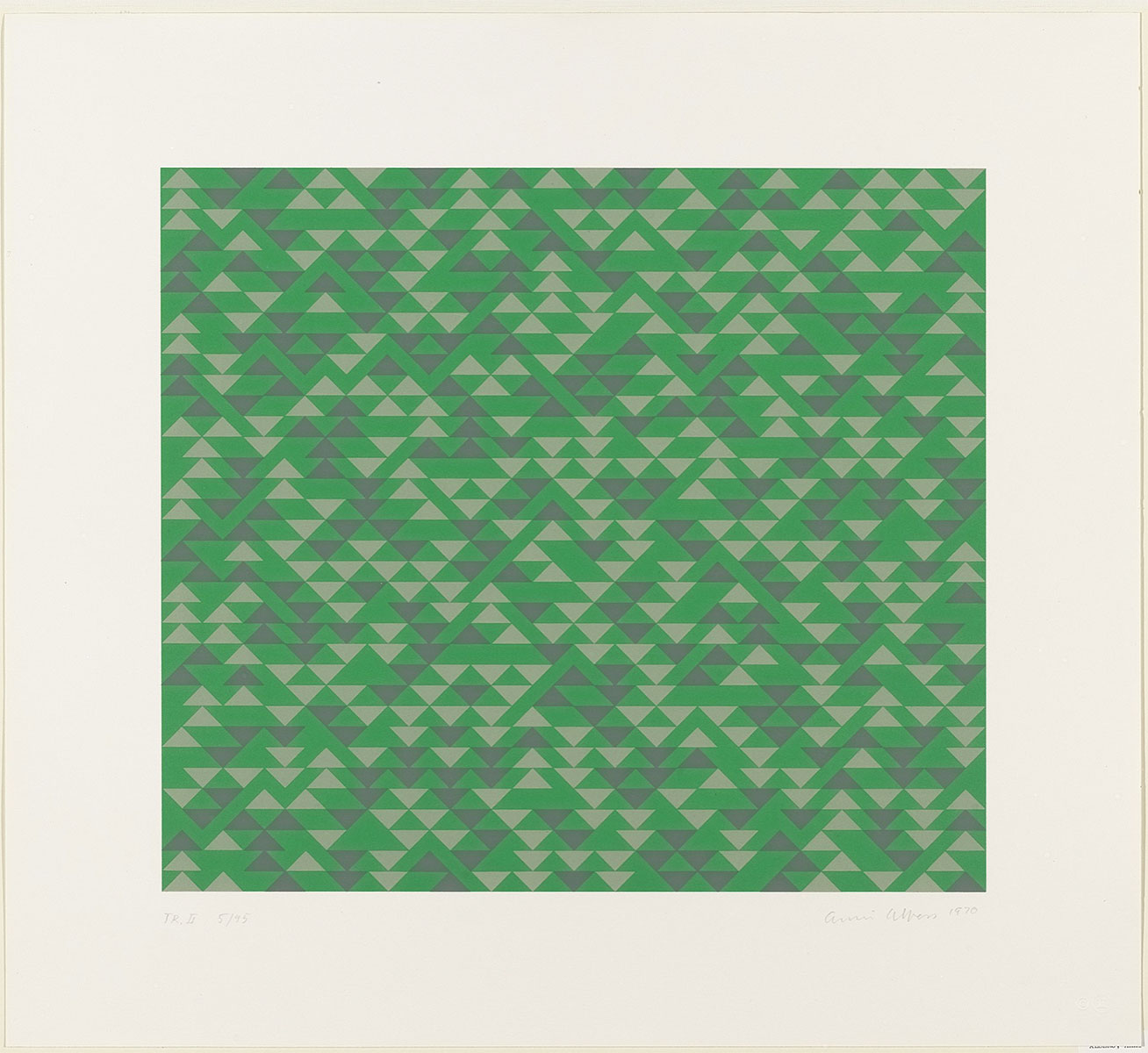

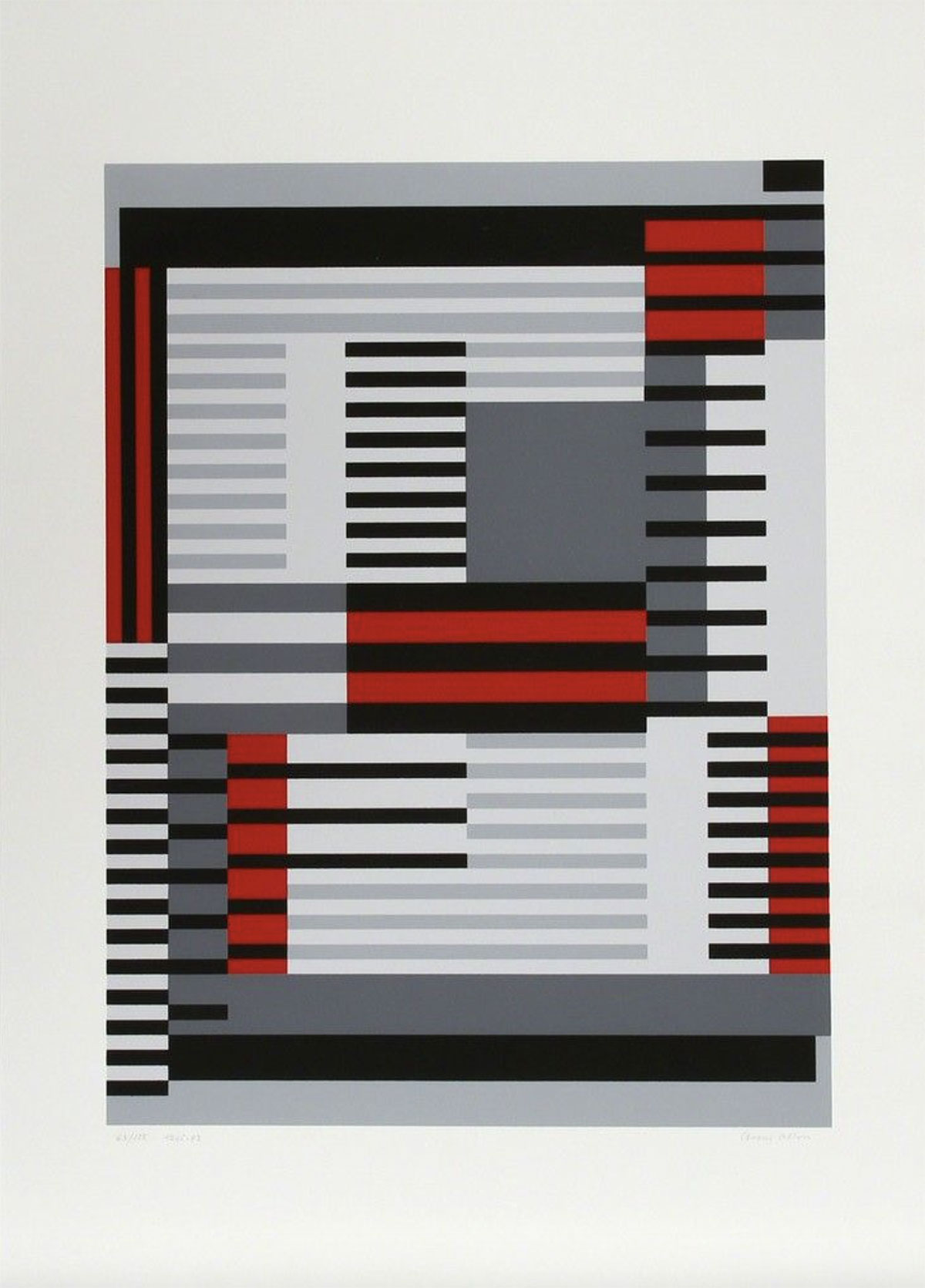

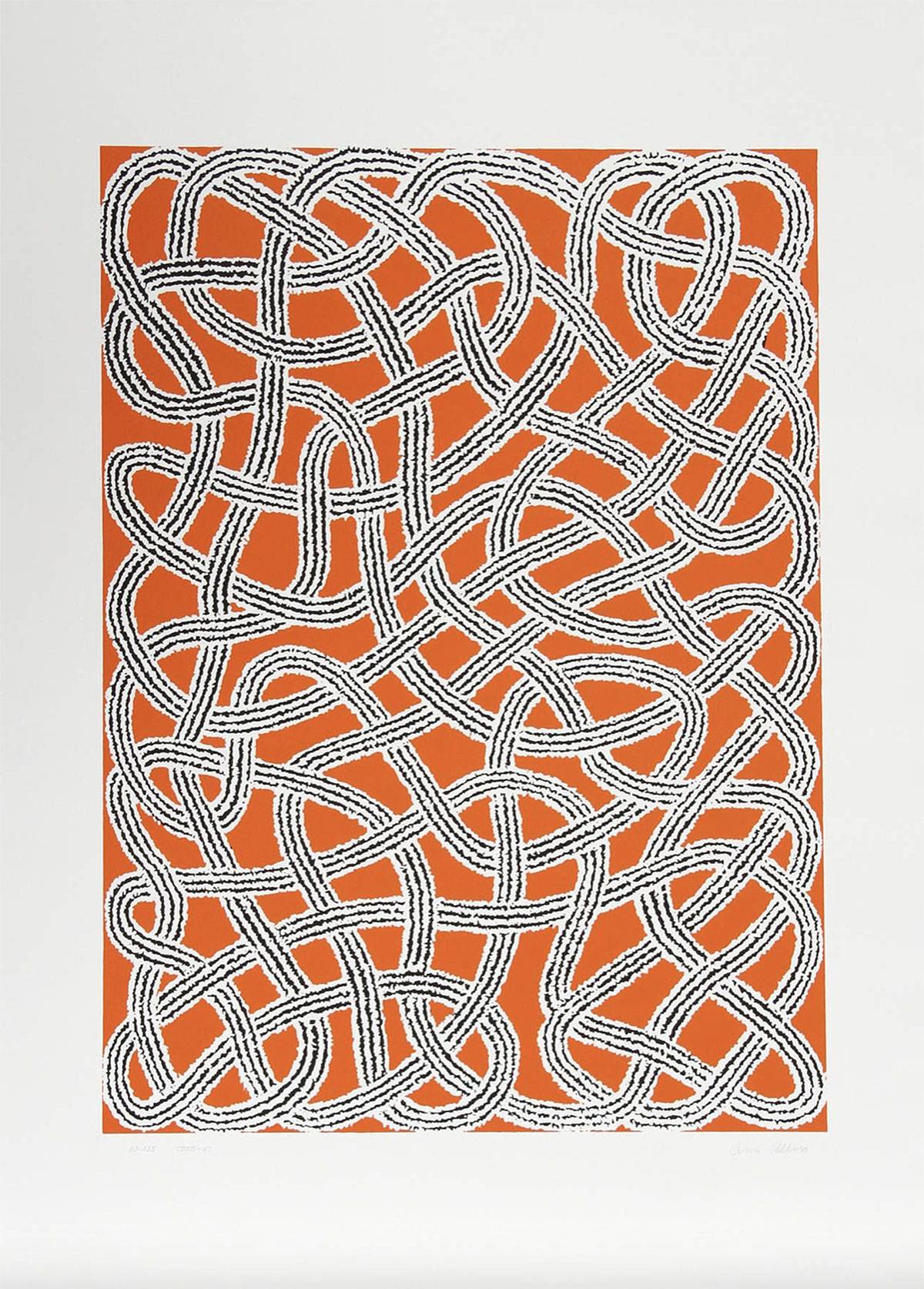

German textile artist and printer Anni Albers (1899-1994), who was born Annelise Elsa Frieda Fleischmann, is credited with fusing traditional craft and fine art. embossing She created a great deal of ink washes for her textile designs and occasionally dabbled in jewellery creation. Numerous wall hangings, curtains, bedspreads, mounted “pictorial” prints, and mass-produced yard material are among her woven creations. She frequently uses both conventional and modern materials in her weavings, freely combining jute, paper, horse hair, and cellophane.

She was fascinated by art and the visual world even as a young child. She painted while she was young and studied impressionism under Martin Brandenburg from 1916 to 1919, but she was greatly discouraged from continuing after meeting with artist Oskar Kokoschka, who asked her sternly “Why do you paint?” after seeing one of her portraits.

Fleischmann ultimately made the decision to enrol in art school despite the difficult living circumstances and frequent difficulties faced by art students. Such a way of life stood in stark contrast to the wealthy and luxurious lifestyle she had become accustomed to. She spent just two months in 1919 studying at the Kunstgewerbeschule in Hamburg before beginning her studies at the Weimar Bauhaus in April of that year.

She spent her first year at the Bauhaus studying under Georg Muche and then Johannes Itten. Fleischmann had a hard time locating her specific workshop at the Bauhaus. Women were not permitted to teach in several subject areas at the school, so during her second year, when she was unable to enrol in a glass workshop with her future husband Josef Albers, Fleischmann reluctantly chose weaving, the sole programme open to female students. Fleischmann had never tried weaving because he thought it was a “sissy” profession. But with the help of her teacher Gunta Stölzl, Fleischmann quickly came to understand the difficulties of tactile construction and started making geometric designs.

Josef Albers, who rose quickly through the Bauhaus ranks to become a “Junior Master,” wed Fleischmann in 1925. After the school relocated to Dessau in 1926, Albers was inspired to create various functionally distinctive textiles that combined qualities of light reflection, sound absorption, durability, and reduced wrinkling and warping tendencies. She received orders for wall hangings and had some of her designs published.

After Walter Gropius left Dessau in 1928, Anni Albers moved into the teaching quarters close to the Klees and the Kandinskys. Anni Albers had previously studied under Paul Klee. The Alberses started their lifelong practise of considerable travel during this time, initially visiting Italy, Spain, and the Canary Islands. The use of a novel material, cellophane, to create a sound-absorbing and light-reflecting wallcovering earned Albers her Bauhaus diploma in 1930.

Albers became one of the only women to hold such a top position at the school when she took over Gunta Stölzl’s position as head of the weaving workshop in 1931 when she departed the Bauhaus.

Under pressure from the Nazi party, the Bauhaus in Dessau was forced to close in 1932. It briefly relocated to Berlin before closing permanently a year later in August 1933. Albers, a Jew, moved to Berlin with her husband and the Bauhaus but then escaped to North Carolina after receiving an invitation from Philip Johnson to work at the experimental Black Mountain College. The couple arrived in the United States in November 1933. Albers taught art as an assistant professor. The emphasis at the school was on “hands-on learning” or “learning by doing.” When Albers relocated classrooms in the early 1940s and the looms were not yet set up, she instructed her students to walk outdoors and gather their own weaving supplies. This was a simple test on substance and structure. Students were able to understand what it could have been like for the early weavers because to Albers’ frequent experiments with various materials in her artwork. Until 1949, Black Mountain employed both Anni and Josef Albers as instructors. Albers’ weavings and other design work were displayed around the US during this time. In 1937, she was granted US citizenship. With one of the Black Mountain students, Alex Reed, Albers co-curated a travelling show on jewellery made at home that debuted at the Willard Gallery in New York City in 1940 and 1941.

Albers had the first solo show of a textile designer at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City in 1949. Albers became recognised as one of the most significant designers of the era thanks to her design exhibition at MoMA, which opened in the fall and toured the US from 1951 to 1953. She also travelled extensively around the Americas and to Mexico during this time, where she developed a passion for collecting pre-Columbian art.

Albers and her husband moved to Connecticut after leaving Black Mountain in 1949, where Albers established up a studio in her house. Following the MoMA exhibition and a commission from Gropius to create a range of bedspreads and other textiles for Harvard, Albers worked on mass-producible fabric patterns, produced the majority of her “pictorial” weavings, and published a dozen articles as well as a collection of her writings called On Designing during the 1950s. She received the Craftsmanship Medal from the American Institute of Architects in 1961.

Albers was given the opportunity to explore with print medium in 1963 while attending her husband’s lecture at the Tamarind Lithography Workshop in Los Angeles. She loved the method right away and devoted the most of her time to lithography and screen printing after that. In 1964, Tamarind invited her back as a fellow. She produced the six prints in the Line Involvements print portfolio at this point. In 1963, Albers produced an article for Britannica, which she later extended for her 1965 book On Weaving. The book provided a potent voice for the American mid-century textile design movement. Her design projects and writings on design contributed to the recognition of Design History as a legitimate field of academic study.

Over the following 20 years, Albers held a few exhibitions of her design work in addition to two significant exhibitions in Germany in 1976. During this time, she also received a number of honorary doctorates and lifetime achievement awards, including the second American Craft Council Gold Medal for “uncompromising excellence” in 1981. 2018 was a collaboration between the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen in Düsseldorf (Germany) and the Tate Modern Museum in London for a retrospective exhibition and book of Albers’s work.

Up to the day of her passing on May 9, 1994, in Orange, Connecticut, Albers continued to speak, travel to Europe and Latin America, design and produce prints, and design. After the pair moved from Black Mountain to Connecticut in 1949, Josef Albers served as the chair of the design department at Yale. He passed away in 1976.

View available Anni Albers prints here.