Buying Art Prints – Advice For Art Collectors

Buying art prints can be a formidable task, for there are numerous issues to be addressed: authenticity, paper, quality of impression, edition size, re-strikes, signatures, states, watermarks, condition, provenance, etc. Here I’ll discuss a few of the many issues that I get lots of questions about; I strongly recommend that anyone with any questions on these or other issues contact me (I’ll try to help); also, you might want to bring your print to a print professional working in a museum print room or university art department, because it’s generally necessary to see a print in person to evaluate it.

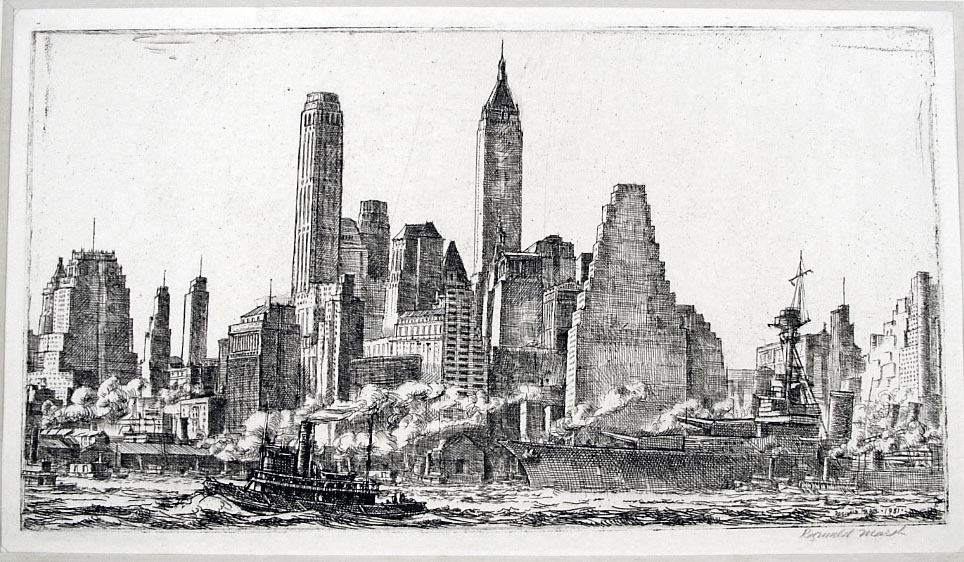

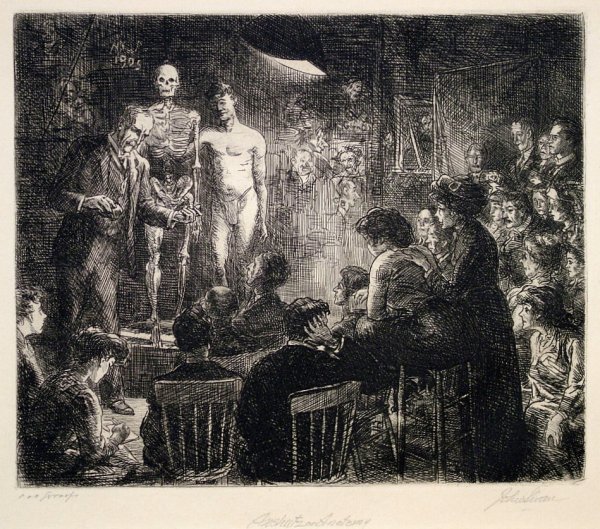

Original Print: An original print in my view is an impression taken from a plate which has been worked on directly by an artist, or where the artist has drawn on a woodblock or lithographic paper with the intention of creating a print. In many cases (e.g., Reginald Marsh‘s etchings, early state Charles Meryon etchings, many Whistler or Rembrandt etchings) the artist also printed each proof. The issue of originality gets cloudy when someone makes a print of another’s work. When this is done it’s referred to as “after,” e.g., an engraving by Cock “after Breugel” (who himself made only one “original print”).

Lifetime Impressions: In general the prints made during an artist’s lifetime are better because the artist approves them, or because the matrix (copper plate, wood block, lithographic stone) is in better condition in the earliest stages of printing, and so would yield a better impression. In many cases it’s difficult to know whether a print is a lifetime impression, especially if the print was printed without changes to the matrix (i.e., in the same state) both lifetime and posthumously.

For example, many Whistler lithographs were printed in the same state before and after his death. It often requires extensive research and connoisseurship to determine whether a print is lifetime – examination of watermarks, print quality, positioning of the print on the paper, paper size, paper type, estate stamps, etc. Sellers claiming to be selling lifetime impressions should be able to prove this claim with a complete and compelling argument.

The print market has been flooded with posthumous impressions (sometimes called posthumous restrikes) of certain artists, such as Rembrandt and Francisco Goya.

Signatures: After about 1870 it became customary for artists to sign prints, generally in pencil at the bottom margin. This is often considered evidence of the artist’s approval of the impression. But many great prints were not signed (e.g., early runs of Picasso’s Vollard Suite). Some artists have signed prints that they did not in fact make (e.g., prints “after” Picasso signed by Picasso); Dali even signed paper before it was printed.

Signatures “in the plate” (woodblock, lithographic stone, copper plate) should not be considered signed or “hand signed,” and such signatures are of little or no consequence. Often, particularly with old master prints, it is preferable to have an impression made before a signature in the plate – this could be an earlier state of the print, when the matrix was in better condition and so would yield a better impression. Signatures can, of course, be faked, and assessing them can be a matter of experience and connoisseurship. Often artists used different signatures during the course of their careers, and the signature type may tell us a lot about when the print was printed.

Certificates of Authenticity: These have been thoroughly discredited in recent years; an inflated-sounding claim of a C of A is often a sign that there is a problem in the wings. Dealers should, however, provide a full description of each print sold, including information on the artist, title, date, image and sheet size, catalog references, state, paper and watermarks, provenance, and any other information of note.

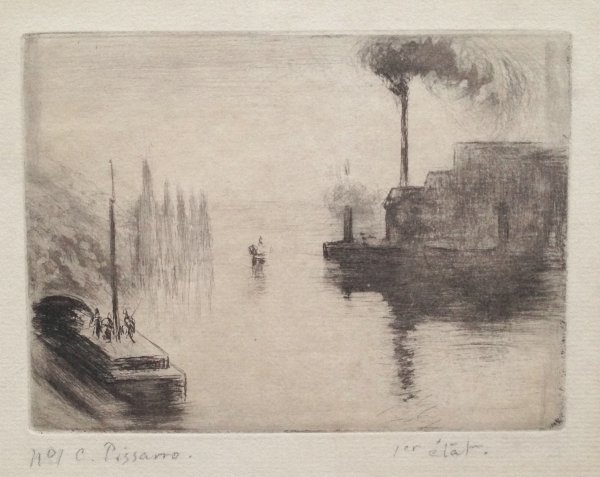

Numbering Prints: Near the end of the 19th C. artists (or sometimes printers, or publishers) started numbering prints, especially those issued in an edition (a group of prints generally printed with some set limit contemplated). Sometimes the prints were simply numbered (e.g., Pissarro wrote No. 1, etc. on prints, and sometimes also wrote the state number; Buhot did too); as editions were issued the numbers were shown as part of an edition (e.g., 15/100).

Numbering sometimes gives clues about the edition. For example, some of Lozowick’s 1972 re-printings of certain lithographs have Roman numerals (e.g. V/X); the earlier editions would not have such numbers. But numbering may not tell much about edition size. For example, Reginald Marsh sometimes numbered prints 13/50 or some such thing, when less than 20 prints were ever made. John Sloan routinely annotated his prints “100 proofs” when the real edition sizes could be a third of that number, or sometimes even more than 100. Artists (and others) are typically given prints “apart from” the edition (artist’s proofs, printer’s proofs, etc.), and if this number is large the “official” edition size may misleadingly underestimate the number of impressions actually printed.

Numbering also need not indicate anything about the quality of a print. Sometimes printers place finished prints in a pile as they’re printed or dried, then the artist signs and numbers them, so the latest prints off the press (and in etching or drypoint, those would typically be the lesser impressions, made when the plate is more worn) have the lowest numbers (and I’ve encountered many higher numbered “better” impressions than lower numbered). But if the prints were dried out all around the print shop or printed at different times and otherwise got out of order and then placed in a pile, there’s no relationship between quality and number. (Of course the idea of signing is that the artist has “approved” the print, but lots of poor printings get signed.) A number or a signature (or a provenance) should not be considered an indicia of print quality – the print itself should be sufficient evidence of its quality!

Condition

Condition is critical to print connoisseurship, and I explore this issue a bit more in my guide on reading a print description (link shown below). Of course tears, especially those affecting the image, matter, as do pin holes or worm holes, foxing (due to fungus) or other discolouration, staining due to light or perhaps poor matting and framing, etc. My sense is that condition has traditionally been so consequential for print buyers because if a print is in any way problematic, it’s generally been possible to find another one that’s not. So the print with the slightest problem may be rejected by the careful collector. But one wonders whether this obsessive-compulsive posture might sometimes go too far. In some cases I’ve seen collectors shy away from prints that are unique impressions – the only ones available or perhaps even known – because they have small condition issues. In these cases, if one wants the print there’s really no choice but to get the one available or do without it, and so it’s reasonable that condition take a lesser role in decision making than when other impressions are readily available.

Print collectors have traditionally worried about margins, the paper outside of the plate mark or the image. If the margins have not been trimmed they are referred to as “full”, and collectors value this. Old master prints tend to be trimmed close to the image. The condition and size of margins would seem to be rather irrelevant to a print’s value, but it does matter, again, perhaps because if a print is trimmed or there’s a problem in the margin, another impression without the problem might be available. Whistler famously trimmed many of his etchings closely, leaving only a small tab for his butterfly signature. He disdained collectors who seemed sometimes to care more about the state of a print’s margins than the quality of it’s image.

Comparing Impressions

Because there are several examples of most prints, collectors can develop a sense of how a print should look by comparing them. Print rooms in museums and libraries often have examples that can be looked at, as do dealers. Although contemporary prints are often printed with the objective of being closely identical to one another, older prints were often printed differently, and of course have fared differently over time. There’s no substitute for examining a number of impressions of a print before selecting one. This is perhaps the most important way one develops print connoisseurship.

Prints and Frames

It’s essential that prints be examined outside of frames to assess condition, collector’s marks, type of paper, watermarks, writing on the front or back of the print, etc. Framing is often a sign that something is wrong with a print – that it has been laid down (glued) to a mat, that its margins are cut or compromised, that it’s been light stained. Often such problems are caused by the framers themselves. Unless you’re more interested in buying the frame than the print, you or your trusted dealer must examine the print outside of the frame. It’s probably a good idea to be wary of prints being sold in frames as well; after all frames are supposed to make prints look good and hide problems. In any case reputable print dealers will always be more than willing to show you their prints outside of frames.

About the author

Harris Schrank is the owner of Harris Schrank Fine Prints (IFPDA) specialising in exceptional examples of fine printmaking – original etchings, engravings, lithographs and woodcuts (from 1490 to 1940) – and highly experienced in buying art prints.