Cobra Art Movement

The CoBrA art movement was possibly the last truly avant-garde movement of the 20th century because of its members’ tenacious opposition to conventional ways of art production and desire to recreate civilization via art.

Constant Nieuwenhuijs, Karel Appel, and Corneille, all members of the Dutch Experimentele Groep, met with their Danish counterpart Asger Jorn on November 8, 1948, in a café on the corner of the rue Saint-Jacques in Paris. Christian Dotremont, a poet and painter from Belgium, served as their leader as they drafted and signed their first manifesto, The Case Was Heard.

The founding ideas that had brought them together at that precise moment were later recalled by Dotremont as follows: “Creation before theory; that art must have roots; materialism which begins with the material; the mark as a sign of wellbeing; spontaneity; experimentation: it was the simultaneity of these elements which created CoBrA.” The group’s name, which was created from the names of the members’ hometowns of Copenhagen, Brussels, and Amsterdam, is credited to Dotrement.

The early CoBrA members established a cooperative network that covered northern Europe, including recently freed cities like Copenhagen, Brussels, and Amsterdam, in an effort to remove themselves from the speculative in-fighting of Paris. They aimed to depart from the rigid forms and constrained palettes that predominated the avant-garde scene at the time and were as hostile to the Academy as they were to the hard geometry of Piet Mondrian and de Stijl.

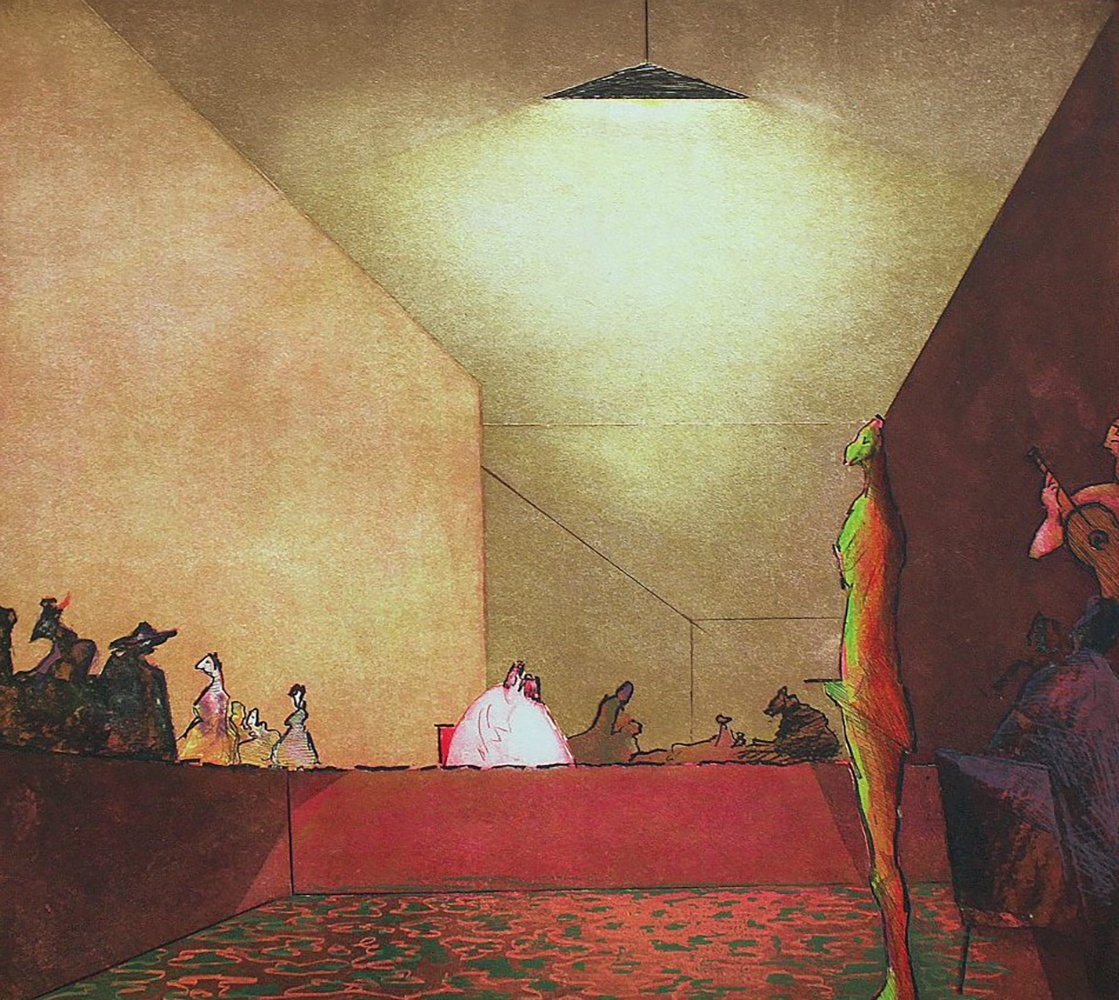

The CoBrA artists created vibrant, cross-disciplinary works that were somewhat influenced by surrealist automatism. Instead of looking to museums or galleries, they resorted to primitive art, children’s drawings, and old Nordic mythology, which combined to form what is now known as the “language of CoBrA.” These resources provided a profound and energising sense of rebirth for Jorn and his coworkers.

The CoBrA ethos placed a strong emphasis on creating collective works like murals and printed publications, such as the namesake CoBrA Journals, as opposed to traditional Western art’s veneration of the lone, artistic genius.

The CoBrA art movement quickly outgrew its beginnings and eventually included about 60 poets, painters, and sculptors from countries including Germany, Sweden, France, England, Denmark, Belgium, and the Netherlands, in addition to those from those countries. The painter Pierre Alechinsky, who first encountered the CoBrA movement’s art in Brussels in 1949, was one of the movement’s early converts.

He immediately swore loyalty to its revolutionary, utopian spirit. He explained that “CoBrA” stands for spontaneity, which is totally opposed to the cold abstraction’s calculations and to any division between free thought and the act of painting freely.

The Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam’s 1949 show is what initially made CoBrA known to a larger worldwide audience. However, the coverage wasn’t entirely favourable: “Botch, Blotch, and Splotch,” read the headline of one Dutch newspaper piece. A reading of CoBrA poems at the show itself caused audience members to fight.

CoBrA would eventually be destroyed by its own ferocious intensity, disbanding in 1951, just three years after it was founded. This was mostly brought on by a profound disagreement over the place of politics in the arts. Constant and Jorn backed the Communist movements that were at the time gaining ground throughout the West, but Dotrement believed that the band should remain wholly uninvolved in politics. We had lost track of whether we were writers or painters by the time it was all over, Dotremont recounted. Alechinsky collapsed… Jorn and I both left for the sanitarium. At that rate, we wouldn’t have survived if we had gone on for another month.

The final CoBrA exhibition, held in Liège, Belgium, in November 1951, featured work by some famous acquaintances, including Joan Miró and Alberto Giacometti, whom Alechinsky humorously referred to as “a few squatters.” The event also featured a reunion of all the important participants.

Despite its brief existence, the CoBrA art movement clearly had an impact on its participants, from Jorn and Enrico Baj, who ventured into unfamiliar territory, to Appel and Alechinsky, who went on to deepen the CoBrA idiom in their works.

The performances of the Japanese Gutai group, the gestural fervour of New York’s Abstract Expressionist movement, and Jean-Michel Basquiat’s vibrant visuals can all be used to trace the origins of CoBrA. With the opening of the CoBrA Museum of Modern Art in Amsterdam in 1995, CoBrA’s significance to the advancement of modern art was solidified.

A whole generation of artists were radicalised by CoBrA, according to Victoria Gramm, an expert at Christie’s in Amsterdam. Their unbridled exuberance, which can be seen in Karel Appel’s swirling impasto and Jorn and Alechinsky’s undulating forms, was essential to the Post-War and European art scenes. These artists continued to travel abroad, start new ensembles, and experiment with various media even after CoBrA split up. They were a veritable whirlwind of inventiveness.