Impressionism Artists

· blog

The Impressionism artists began in 1874 when a group of artists known as the Anonymous Society of Painters, Sculptors, Printmakers, etc. organised an exhibition in Paris. Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, and Camille Pissarro were among its original members. Only the group’s rejection of the official yearly Salon, for which a jury of painters from the Académie des Beaux-Arts chose works of art and presented medals, served as its unifying principle. Despite using various painting techniques, the independent artists shared a common appearance with their contemporaries. More progressive writers commended their work for its portrayal of contemporary life, while conservative critics criticised it for having an incomplete, sketch-like appearance. For instance, Edmond Duranty referred to their depiction of contemporary subject matter in a properly new style as a revolution in painting in his 1876 article La Nouvelle Peinture (The New Painting). Although some of them later acquired the term by which they would eventually be known, the Impressionists, the exhibiting collective avoided picking a moniker that would suggest a united movement or school. Their work is recognised today for its modernity, which is shown in its rejection of traditional aesthetics, assimilation of cutting-edge concepts and ideas, and portrayal of contemporary life.

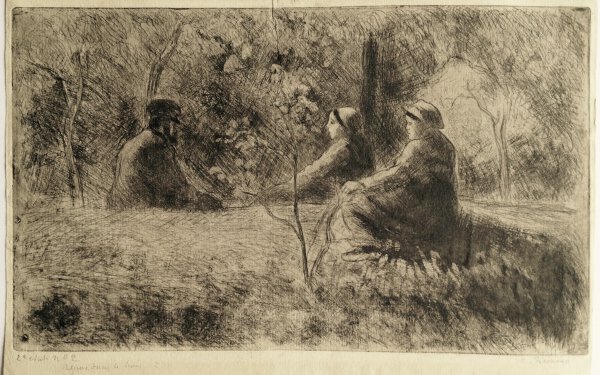

The Impressionist artists and movement was named after Claude Monet’s 1874 painting Impression, Sunrise (Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris), which the critic Louis Leroy claimed was only a “impression” and not a full work of art. It exemplifies the methods that many of the self-taught artists adopted: short, broken brushstrokes that hardly transmit forms, clean, unmixed colours, and a concentration on the effects of light. Impressionists frequently depicted shadows and highlights in colour rather than using the neutral tones of white, grey, and black. The loose brushstrokes of the artists create the impression of spontaneity and ease, concealing their frequently meticulously planned compositions. Even in the formal Salon, this seemingly informal approach was widely regarded as the new vocabulary for portraying contemporary life.

Along with their innovative technique, Impressionist paintings’ vivid colours startled viewers used to the more subdued hues of academic painting. Many of the independent artists made the decision to forgo using the heavy golden varnish that painters often employed to soften their creations. Additionally, the actual paints were more brilliant. Synthetic blue, green, and yellow pigments, which painters had never used previously, were developed in the nineteenth century for use in artist’s paints.

The Impressionism artists, especially Monet and Auguste Renoir, were drawn to depictions of suburban and country leisure outside of Paris. Several of them spent all or a portion of the year in the nation. Parisians practically rushed into the countryside every weekend thanks to new railway lines that radiated out from the city, making travel so convenient. While some Impressionism artists, like Pissarro, at Pontoise concentrated on the daily lives of the local people, the majority preferred to portray the pastoral pleasures of the holidaymakers. The thriving boating and swimming establishments in these areas became popular motifs. Impressionist landscapes, which are heavily featured in their work, were also modernised through the use of fresh compositions, light effects, and colour. By incorporating railroads and factories—signs of creeping industrialisation that would have seemed incongruous to the Barbizon artists of the previous generation—Monet in particular highlighted the modernisation of the environment.

Paris itself, restored between 1853 and 1870 under Emperor Napoleon III, was perhaps the epicentre of modernity in the late nineteenth century. His prefect, Baron Haussmann, devised the designs, demolishing outdated structures to make way for more open space and a safer, cleaner city. The Siege of Paris during the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871), which necessitated restoring the city’s damaged areas, also contributed to its new appearance. The newly restored city was eagerly painted by impressionists like Pissarro and Gustave Caillebotte, who used their brand-new aesthetic to capture its broad boulevards, public parks, and opulent structures. Some people concentrated on the cityscapes, while others directed their attention to the city’s residents. They had a tonne of material for their urban landscapes thanks to the post-Franco-Prussian War population increase in Paris. The blending of social strata in public places was a defining feature of these scenes. Degas and Caillebotte concentrated on portraying working people, including musicians and dancers in addition to labourers. Others, like Mary Cassatt and Berthe Morisot, painted the affluent classes. The Impressionists also depicted novel leisure activities, such as dances, cafés, popular concerts, and theatre (such as Cassatt’s 1878 painting In the Loge, now housed in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston). The painters of urban scenes used a strategy analogous to that of Naturalist authors like Émile Zola, portraying ephemeral yet characteristic moments in the lives of persons they witnessed. The Art Institute of Chicago’s 1877 Paris Street, Rainy Day by Caillebotte is a prime example of how these artists abandoned romantic portrayals and specific storylines in favour of an objective, detached viewpoint that just conveys what is happening.

Over the course of the eight shows the independent collective staged between 1874 and 1886, its membership fluctuated, with the number of participating artists ranging from nine to thirty. The oldest artist, Pissarro, was the only one to participate in all eight exhibitions; Morisot took part in seven. Even as early as 1867, plans for an independent exhibition were being explored, but the Franco-Prussian War got in the way. The war claimed the life of the leader of the effort, the painter Frédéric Bazille. Different artists led subsequent exhibits. The contributors fluctuated as a result of the artists’ philosophical and political disagreements, which caused acrimonious arguments and rifts. Even more conservative artists who flat-out refused to submit their work to the Salon jury were represented in the shows. Paul Cézanne and Paul Gauguin, whose latter styles sprang out of their early work with the Impressionists, also took part in the independent exhibits.

A new era in avant-garde art began in 1886 with the final of the independent exhibits. Few of the participants were still creating in an instantly recognisable Impressionist style by this point. The majority of the core members were evolving into new, distinct personalities, which led to rifts in the group’s shaky cohesion. Paul Signac and Georges Seurat were encouraged to participate by Pissarro, who also adopted their new Neo-Impressionism style that was centred on pure colour points. Young Gauguin was dabbling in primitive art. Odilon Redon, a budding Symbolist, also contributed, albeit his approach was unique from everyone else’s. Some of the main members, including Monet and Renoir, showed in locations where their works were more likely to sell due to the group’s artistic and philosophical dispersion and the necessity for guaranteed revenue.

It is challenging to categorise the Impressionist movement due to its complexity and diversity of players. Its existence does indeed appear as brief as the light effects it aimed to capture. Even yet, the Impressionism artists and movement had long-lasting effects since it served as a model for later avant-garde art in Europe due to its embrace of modernity.

View prints by Impressionism artists here.