Op Art

· blog

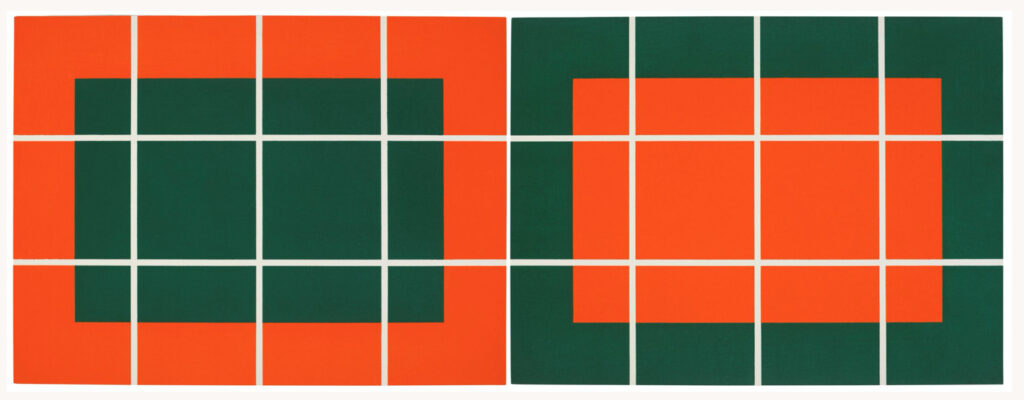

Op art is unique. For millennia, artists have been fascinated by the nature of perception, as well as optical effects and illusions. They have long been a primary focus of art, just as historical or literary topics have been. However, in the 1950s, these preoccupations grew into a movement when they were combined with new technological and psychological interests. Abstract patterns built with a dramatic contrast of foreground and background – often in black and white for maximum contrast – are commonly used in Op art to achieve effects that confuse and excite the eye. Initially, Op and Kinetic Art shared the field, with Op artists drawn to virtual movement and Kinetic artists to the promise of genuine motion.

In 1955, Le Mouvement, a group exhibition at Galerie Denise Rene, established both styles. It drew a large international following, and after being honoured with a survey exhibition, The Responsive Eye, at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1965, it piqued the public’s interest and sparked a fashion and media obsession for Op designs. It appeared to many to be the ideal style for an era marked by the advancement of science, including developments in computing, aerospace, and television. However, art critics were never as enthusiastic about it, dismissing its effects as gimmicks, and it has remained soiled by such dismissals to this day.

Artist and journalist Donald Judd may have coined the term “Op art” in a review of Julian Stanczak’s “Optical Paintings” exhibition. However, it became well-known after appearing in a 1964 Time magazine article, and its origins went back many years. Its origins can be traced back to 19th-century art and colour theory, particularly Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s colour writings and Georges Seurat’s Neo-impressionist paintings.

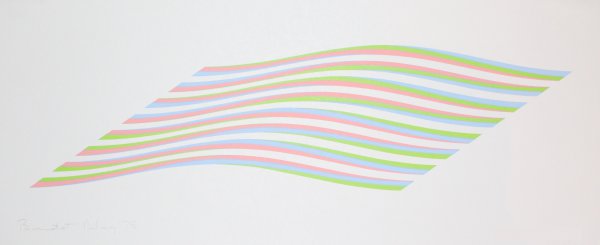

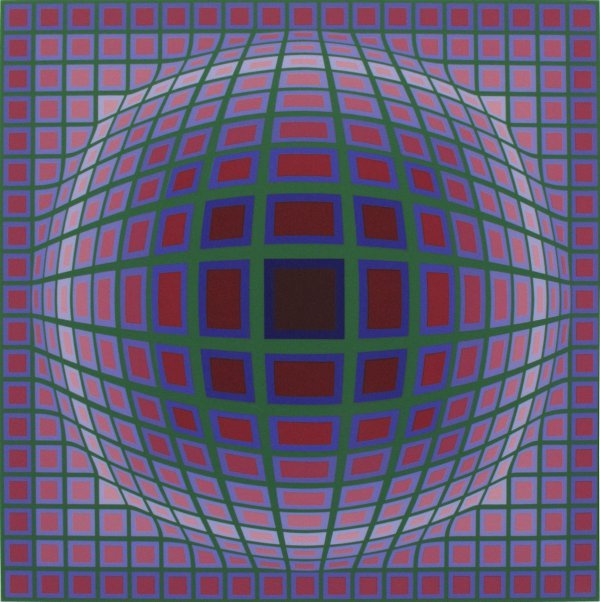

However, the Op style we know today arose from the work of Victor Vasarely, who first experimented with odd perceptual effects in certain 1930s works. The group show Le Mouvement at Galerie Denise Rene in Paris in 1955, and later a series of international shows investigating what was known as the “New Tendency,” gave it a boost. Vasarely’s work quickly gained a worldwide following: Bridget Riley, who, like Vasarely, had worked in advertising, adopted the style (quickly rising to even greater notoriety than Vasarely), and several South American artists, mostly based in Paris, also created in the Op Style.

The Responsive Eye, a 1965 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, featured 123 paintings and sculptures by artists such as Victor Vasarely, Bridget Riley, Frank Stella, Carlos Cruz-Diez, Jesus Rafael Soto, and Josef Albers, and represented the apex of the movement’s popularity. The clash of art and science piqued the interest of many museum visitors, while critics such as Clement Greenberg were adamantly opposed to the concept. The inclusion of artists like Frank Stella, whose concerns were so distinct from Vasarely’s, in exhibits like The Responsive Eye threw doubt on the movement, since the title looked almost too broad to be useful or plausible.