Pablo Picasso Prints: A Collector’s Guide

Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) is of course most famous for his enduringly popular paintings. His career was impressive, having started creating prints in 1899 as a teenager. He then continued his works right up to his very last one 1972 at the age of 90.

Picasso had a multi-disciplinary approach to moulding his images. He spend a lot of time of energy making his prints, deeming it to be just as important as the creative process itself. He would also often work out ideas in print and paint simultaneously. Pablo Picasso prints were made using a number of different printmaking techniques.

Early experiments: The Saltimbanque Suite, Ambrose Vollard

Picasso started creating prints in earnest in 1904-05, with a set of 14 etchings based around the theme of circus figures. These became know as his ‘Saltimbanque Suite’, principally apparently made to quickly gain some much-needed funds.

The Saltimbanque Suite includes one of the artist’s most popular pieces “Le repas frugal” depicting a starving man and woman at an almost empty dinner table. They’re looking in opposite directions, although he has his arm around her in comfort.

1930s: Roger Lacourière and the Vollard Suite

Picasso’s earliest experiments involved the use of particularly large etching needles, and the introduction of nail varnish and suet to bring about some unusual results.

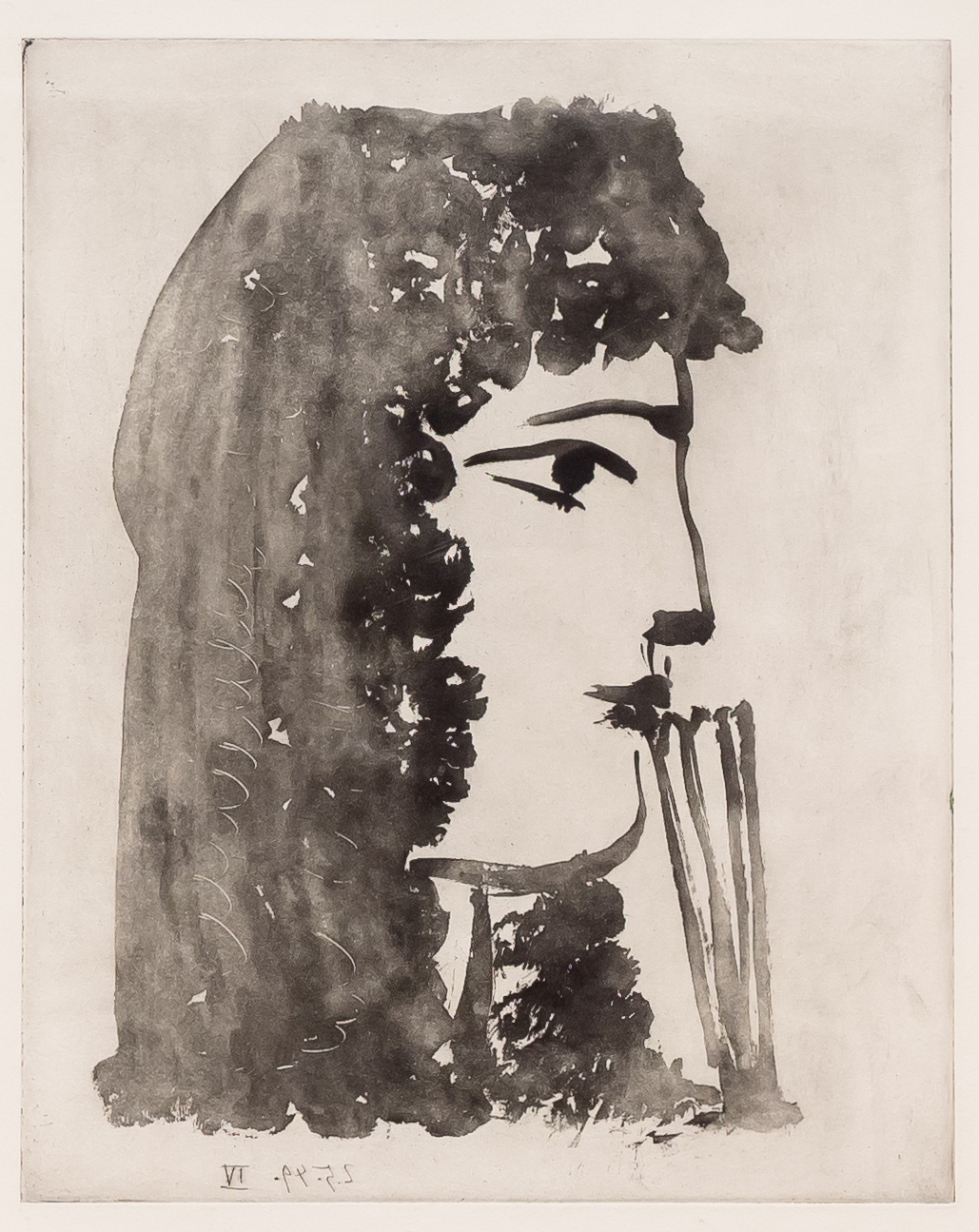

One of his most successful advances came in 1934 after he started to work with Roger Lacourière. The artist adopted a method referred to as the ‘sugar-lift aquatint’. This meant using a sugary solution that created painterly, very tonal effects, like those we can see in Faune devoilant une femme (Faun Unveiling a Sleeping Woman).

That work was one of 100 etchings that made up the ‘Vollard Suite’, one of Picasso’s most famous series. The series was named after Ambroise Vollard, for whom it was made, between 1930 and 1937 – in exchange for two paintings the dealer owned by Cézanne and Renoir.

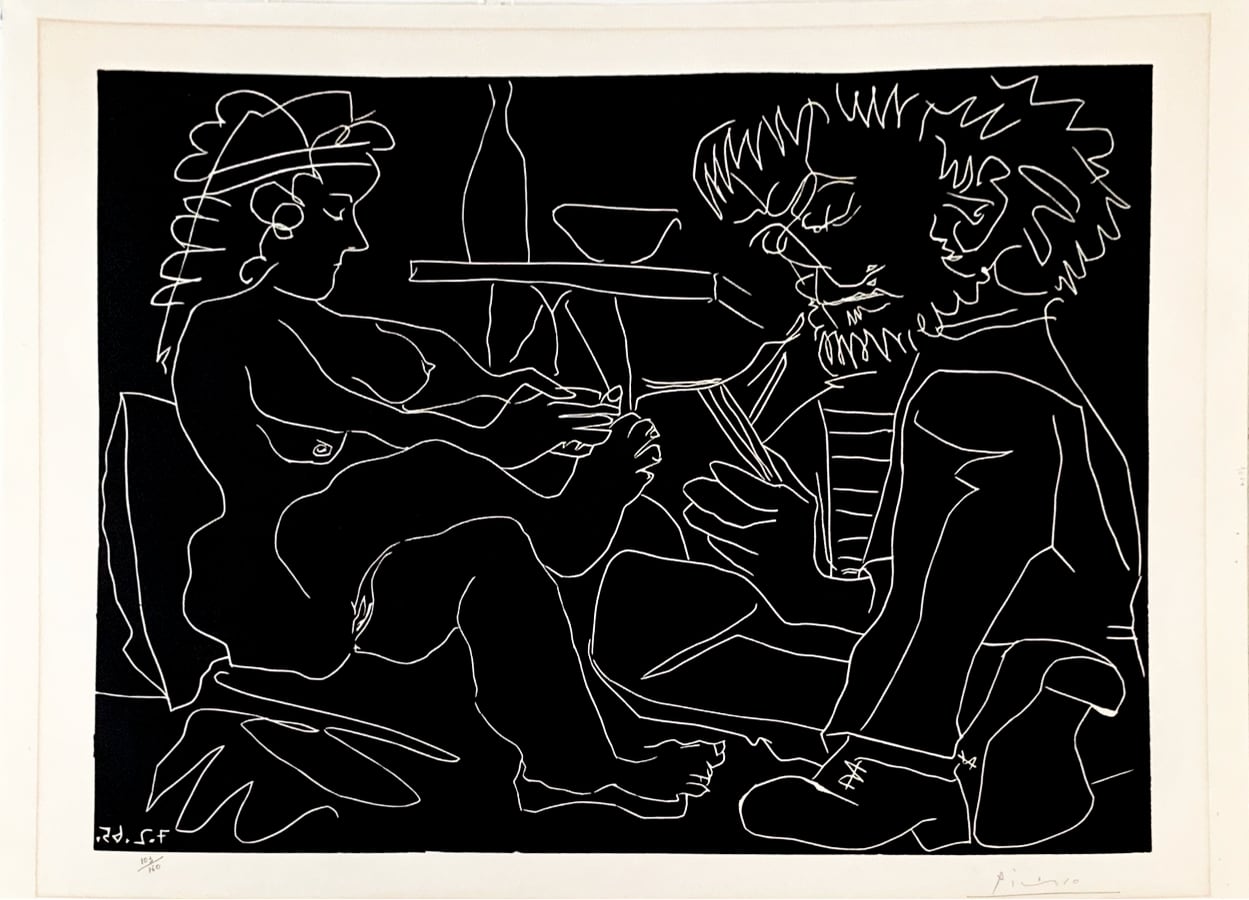

Post-1945: Fernand Mourlot, lithography and The Bull

With Paris newly liberated after World War II, Picasso found himself inundated with visitors and took refuge in the studio of lithographer Fernand Mourlot. Now working together, they created some 400 lithographs, to include several portraits of Françoise Gilot, Picasso’s latest lover.

During this time, Picasso started to use his fingers to make marks, rather than using a brush or lithographic crayon. Picasso also appreciated the way lithography – more than other printmaking processes – allowed him to easily make changes to images as he went along.

1950s: Hidalgo Arnéra and linocut

Picasso moved to the Côte d’Azur in the 1950s. Lithography and etching were more difficult to practice there, as they required specialist equipment that wasn’t easy to get hold of. After a while however, he came across a local printer named Hidalgo Arnéra, whose specialism was in posters – and it was Arnéra who introduced him to the linocut process.

The linocut process involves cutting separate pieces of linoleum for each of the colours required. Picasso, however, decided to make this process more efficient by inventing the ‘reduction method’, meaning just a single piece of linoleum could be used instead.

1960s: Aldo and Piero Crommelynck and the 347 Suite

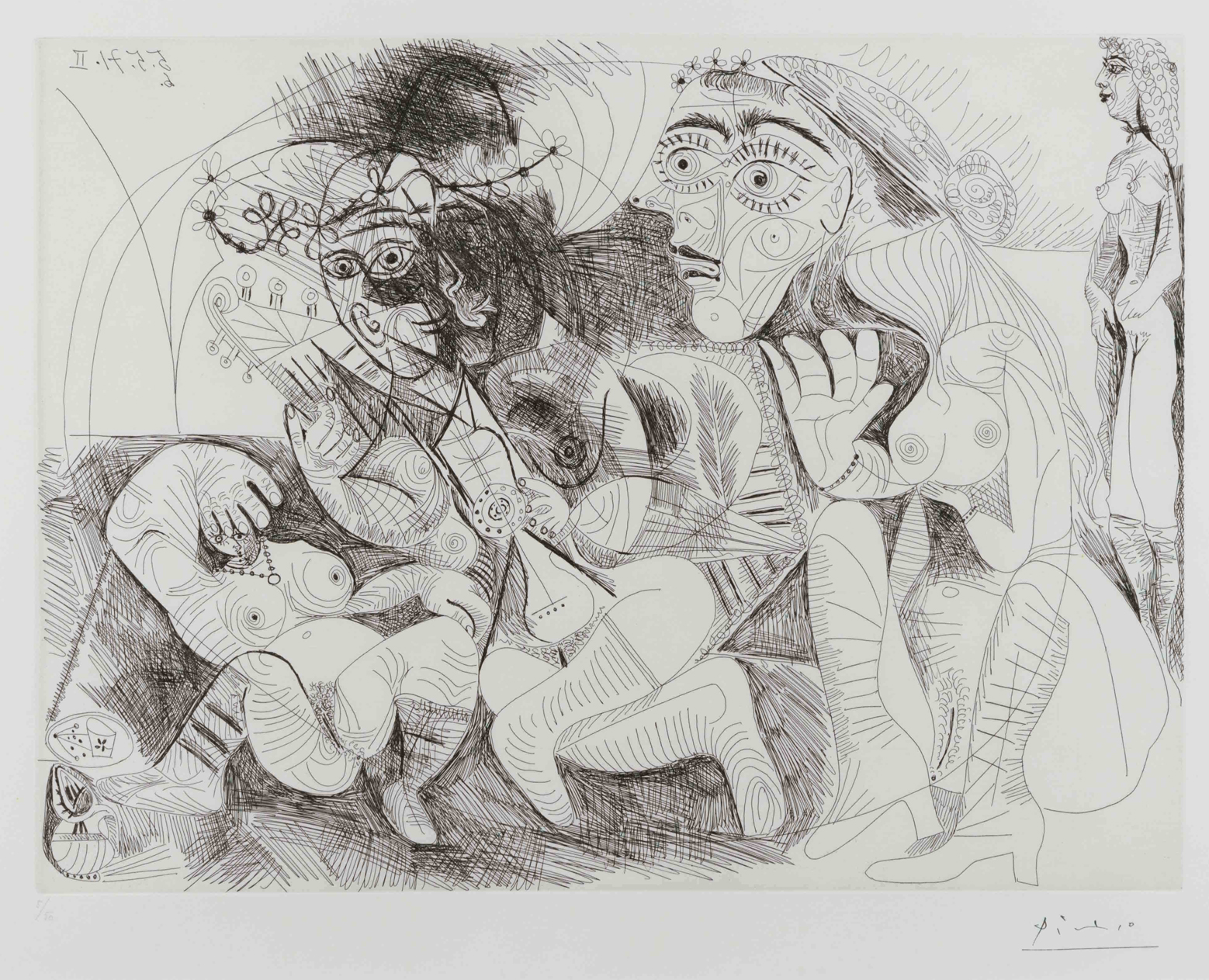

In 1963, the printmaking brothers Aldo and Piero Crommelynck wanted so much to collaborate with Picasso that they moved from Paris and set up an etching studio in the village of Mougins, where the artist lived at the time.

With the Crommelyncks’ help, Picasso came to produce hundreds of etchings that signified not just a final hurrah, but the pinnacle of his career in fact.

They include the series known as the ‘347 Suite’ produced in 1968. It was named after the number of etchings in it and was produced by an 86-year-old Picasso in a remarkable burst of intense creation.

Picasso created his very last series – the ‘156 Suite’ – after turning 90. It was completing in June 1972, less than a year before he died.

A life in printmaking

Picasso’s printmaking career lasted more than seven decades. Like his paintings, his prints can be interpreted autobiographically, to a large extent. His wives and lovers feature regularly, as do certain political references of the time, such as in the pair of prints lampooning General Franco, Sueño y Mentira de Franco I & II.