Richard Diebenkorn Prints In The 1960s

Richard Diebenkorn began to have a measure of success with his artwork during the mid to late 1950s. He was included in several group shows and had several solo exhibits. In 1960, a mid-career retrospective was presented by the Pasadena Art Museum (now the Norton Simon Museum). That autumn, a variation of the show moved to the California Palace of the Legion of Honor in San Francisco. In summer 1961, while a visiting instructor at UCLA, Diebenkorn first became acquainted with printmaking when his graduate assistant introduced him to the printmaking technique of drypoint. Also while in Southern California, Diebenkorn was a guest at Tamarind Lithography Workshop (now the Tamarind Institute), where he worked on a suite of prints that was completed in 1962.

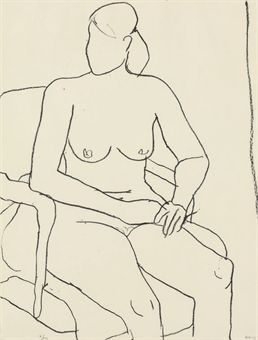

Upon his return to Berkeley in fall 1961, Diebenkorn began seriously exploring drypoint and printmaking with Kathan Brown at her newly established fine arts printing press, Crown Point Press. In 1965, Crown Point Press printed and published an edition of thirteen bound volumes and twelve unbound folios of Diebenkorn’s first suite of prints, 41 Etchings Drypoints. This project was the first publication of Crown Point’s catalogue). Diebenkorn would not do any more etching again until 1977, when Brown renewed their artistic relationship. From then until 1992, Diebenkorn returned almost yearly to Crown Point Press to produce work.

Also in the fall of 1961, Diebenkorn became a faculty member at the San Francisco Art Institute, where he taught periodically until 1966. He also taught intermittently during these years at a number of other colleges, including the California College of Arts and Crafts and Mills College in Oakland, the University of Southern California (USC), the University of Colorado, Boulder, and the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA).

In September 1963, Diebenkorn was named the first artist-in-residence at Stanford University in Palo Alto, California, an appointment that lasted until June 1964. His only responsibility in this position was to produce art in a studio provided by the university. Students were allowed to visit him in the studio during scheduled times. Though he created few paintings during his time at Stanford, he did produce a large number of drawings. Stanford presented an extensive show of these drawings at the end of his residency.

From fall 1964 to spring 1965, Diebenkorn traveled through Europe, and he was granted a cultural visa to visit important Soviet museums and view their holdings of Matisse’s paintings. When he returned to painting in the Bay Area in mid-1965, his resulting works summed up all that he had learned from more than a decade as a leading figurative painter.

The Henri Matisse paintings French Window at Collioure, and View of Notre-Dame, both from 1914, exerted tremendous influence on Richard Diebenkorn’s Ocean Park paintings. According to art historian Jane Livingston, Diebenkorn saw both Matisse paintings in an exhibition in Los Angeles in 1966, and they had an enormous effect on him and his work. Livingston said about the January 1966 Matisse exhibition that Diebenkorn saw in Los Angeles,

It is difficult not to ascribe enormous weight to this experience for the direction his work took from that time on. Two pictures he saw there reverberate in almost every Ocean Park canvas. View of Notre Dame and French Window at Collioure, both painted in 1914, were on view for the first time in the US.

Livingston went on to say, “Diebenkorn must have experienced French Window at Collioure as an epiphany.”

In September 1966, Diebenkorn moved to Santa Monica, California, and took up a professorship at UCLA. He moved into a small studio space in the same building as his old friend from the Bay Area, Sam Francis. In winter 1966–67, he returned to abstraction, this time in a distinctly personal, geometric style that clearly departed from his early abstract expressionist period. The Ocean Park series, begun in 1967 and developed for the next 18 years, became his most famous work and resulted in approximately 135 paintings. Based on the aerial landscape and perhaps the view from the window of his studio, these large-scale abstract compositions were named after a community in Santa Monica, where he had his studio.