Japanese Woodblock Prints

In 764 the Empress Kōken commissioned one million small wooden pagodas, each containing a small woodblock scroll printed with a Buddhist text (Hyakumantō Darani). These were distributed to temples around the country as thanks for the suppression of the Emi Rebellion of 764. These are the earliest examples of woodblock prints known, or documented, from Japan.

By the eleventh century, Buddhist temples in Japan produced printed books of sutras, mandalas, and other Buddhist texts and images. For centuries, printing was mainly restricted to the Buddhist sphere, as it was too expensive for mass production, and did not have a receptive, literate public as a market. However, an important set of fans of the late Heian period (12th century), containing painted images and Buddhist sutras, reveal from loss of paint that the underdrawing for the paintings was printed from blocks. In the Kamakura period from the 12th century to the 13th century, many books were printed and published by woodblock printing at Buddhist temples in Kyoto and Kamakura.

Western style movable type printing-press was brought to Japan by Tenshō embassy in 1590, and was first printed in Kazusa, Nagasaki in 1591. However, western printing-press were discontinued after the ban on Christianity in 1614. The printing-press seized from Korea by Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s forces in 1593 was also in use at the same time as the printing press from Europe. An edition of the Confucian Analects was printed in 1598, using a Korean moveable type printing press, at the order of Emperor Go-Yōzei.

Tokugawa Ieyasu established a printing school at Enko-ji in Kyoto and started publishing books using domestic wooden movable type printing-press instead of metal from 1599. Ieyasu supervised the production of 100,000 types, which were used to print many political and historical books. In 1605, books using domestic copper movable type printing-press began to be published, but copper type did not become mainstream after Ieyasu died in 1616.

The great pioneers in applying movable type printing press to the creation of artistic books, and in preceding mass production for general consumption, were Honami Kōetsu and Suminokura Soan. At their studio in Saga, Kyoto, the pair created a number of woodblock versions of the Japanese classics, both text and images, essentially converting emaki (handscrolls) to printed books, and reproducing them for wider consumption. These books, now known as Kōetsu Books, Suminokura Books, or Saga Books, are considered the first and finest printed reproductions of many of these classic tales; the Saga Book of the Tales of Ise (Ise monogatari), printed in 1608, is especially renowned.

Despite the appeal of moveable type, however, craftsmen soon decided that the running script style of Japanese writings was better reproduced using woodblocks. By 1640 woodblocks were once again used for nearly all purposes. After the 1640s, movable type printing declined, and books were mass-produced by conventional woodblock printing during most of the Edo period.

A two piece nishiki-e (colored woodblock print) series depicting a class at terakoya (private educational school).

The mass production of woodblock prints in the Edo period was due to the high literacy rate of Japanese people in those days. The literacy rate of the Japanese in the Edo period was almost 100% for the samurai class and 50% to 60% for the chōnin and nōmin (farmer) class due to the spread of private schools terakoya. There were more than 600 rental bookstores in Edo, and people lent woodblock-printed illustrated books of various genres. While the Saga Books were printed on expensive paper, and used various embellishments, being printed specifically for a small circle of literary connoisseurs, other printers in Edo quickly adapted the conventional woodblock printing to producing cheaper books in large numbers, for more general consumption. The content of these books varied widely, including travel guides, gardening books, cookbooks, kibyōshi (satirical novels), sharebon (books on urban culture), kokkeibon (comical books), ninjōbon (romance novel), yomihon, kusazōshi, art books, play scripts for the kabuki and jōruri (puppet) theatre, etc. The best-selling books of this period were Kōshoku Ichidai Otoko (Life of an Amorous Man) by Ihara Saikaku, Nansō Satomi Hakkenden by Takizawa Bakin, and Tōkaidōchū Hizakurige by Jippensha Ikku, and these books were reprinted many times.

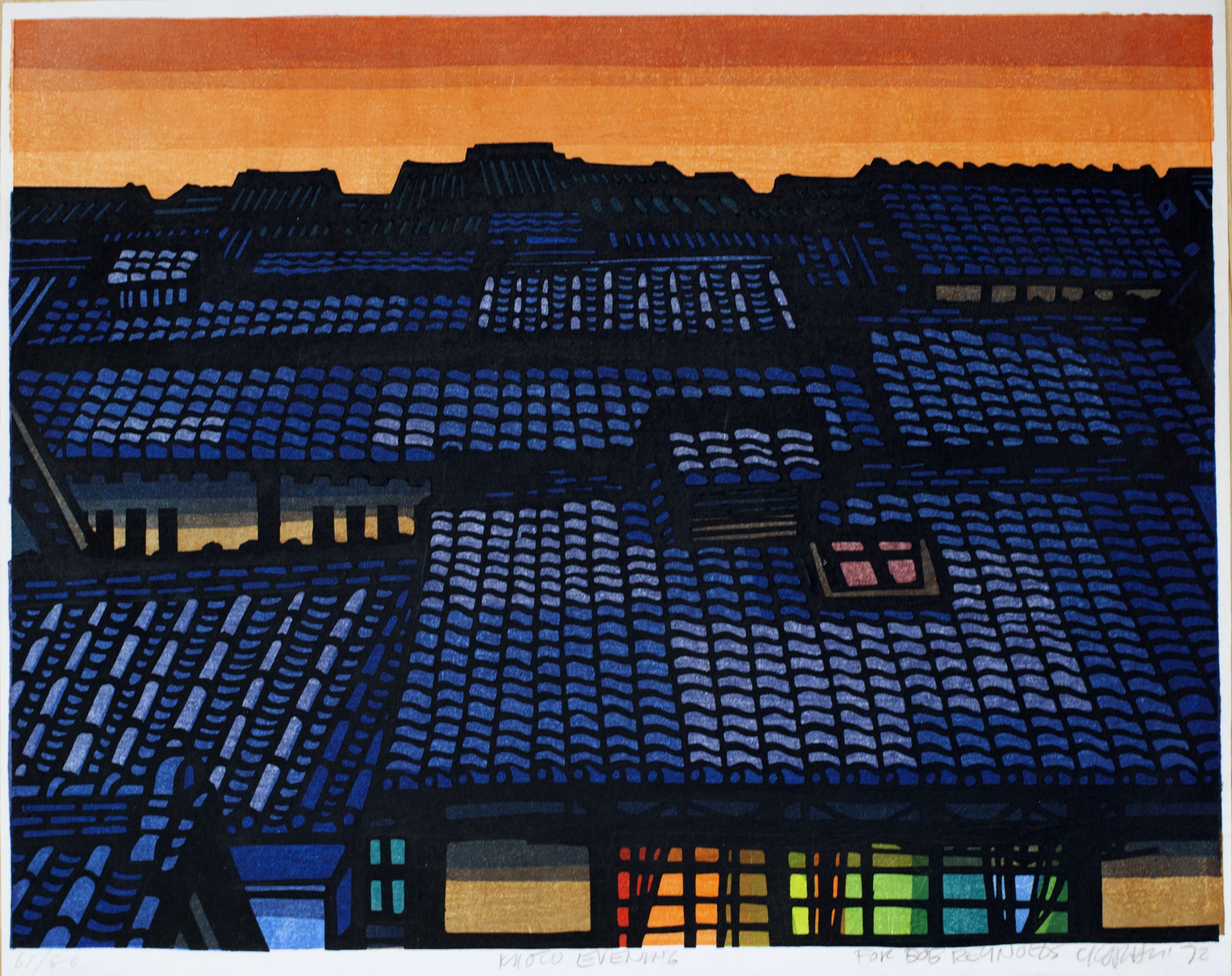

From the 17th century to the 19th century, ukiyo-e depicting secular subjects became very popular among the common people and were mass-produced. ukiyo-e is based on kabuki actors, sumo wrestlers, beautiful women, landscapes of sightseeing spots, historical tales, and so on, and Hokusai and Hiroshige are the most famous artists. In the 18th century, Suzuki Harunobu established the technique of multicolor woodblock printing called nishiki-e and greatly developed Japanese woodblock printing culture such as ukiyo-e. Ukiyo-e influenced European Japonisme and Impressionism. Yoshitoshi was called the last great ukiyo-e master, and his cruel depictions and fantastic expressions influenced later Japanese literature and anime. The price of one ukiyo-e at that time was about 20 mon, and the price of a bowl of soba noodles was 16 mon, so the price of one ukiyo-e was several hundred yen to 1000 yen in today’s currency.

Many publishing houses arose and grew, publishing both books and single-sheet Japanese woodblock prints. One of the most famous and successful was Tsuta-ya. A publisher’s ownership of the physical woodblocks used to print a given text or image constituted the closest equivalent to a concept of “copyright” that existed at this time. Publishers or individuals could buy woodblocks from one another, and thus take over the production of certain texts, but beyond the ownership of a given set of blocks (and thus a very particular representation of a given subject), there was no legal conception of the ownership of ideas. Plays were adopted by competing theatres, and either reproduced wholesale, or individual plot elements or characters might be adapted; this activity was considered legitimate and routine at the time.

After the decline of ukiyo-e and introduction of modern printing technologies, woodblock printing continued as a method for printing texts as well as for producing art, both within traditional modes such as ukiyo-e and in a variety of more radical or Western forms that might be construed as modern art. In the early 20th century, shin-hanga that fused the tradition of ukiyo-e with the techniques of Western paintings became popular, and the works of Hasui Kawase and Hiroshi Yoshida gained international popularity. Institutes such as the “Adachi Institute of Woodblock Prints” and “Takezasado” continue to produce ukiyo-e prints with the same materials and methods as used in the past.