The Nazi Campaign Against Degenerate Art

This article commemorates the 80th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz.

The Nazi Campaign Against Degenerate Art

The term “degenerate art” (Entartete Kunst) emerged in Nazi Germany as a politically charged designation for modern art forms that the regime deemed harmful to German society. While the Nazis popularized this term in the 1930s, its ideological roots can be traced to the late 19th century, when conservative cultural critics began associating modern artistic movements with moral and social decline. This perspective was deeply intertwined with pseudo-scientific theories about racial degeneration and cultural purity that gained traction in European intellectual circles.

Definition and Targeted Movements

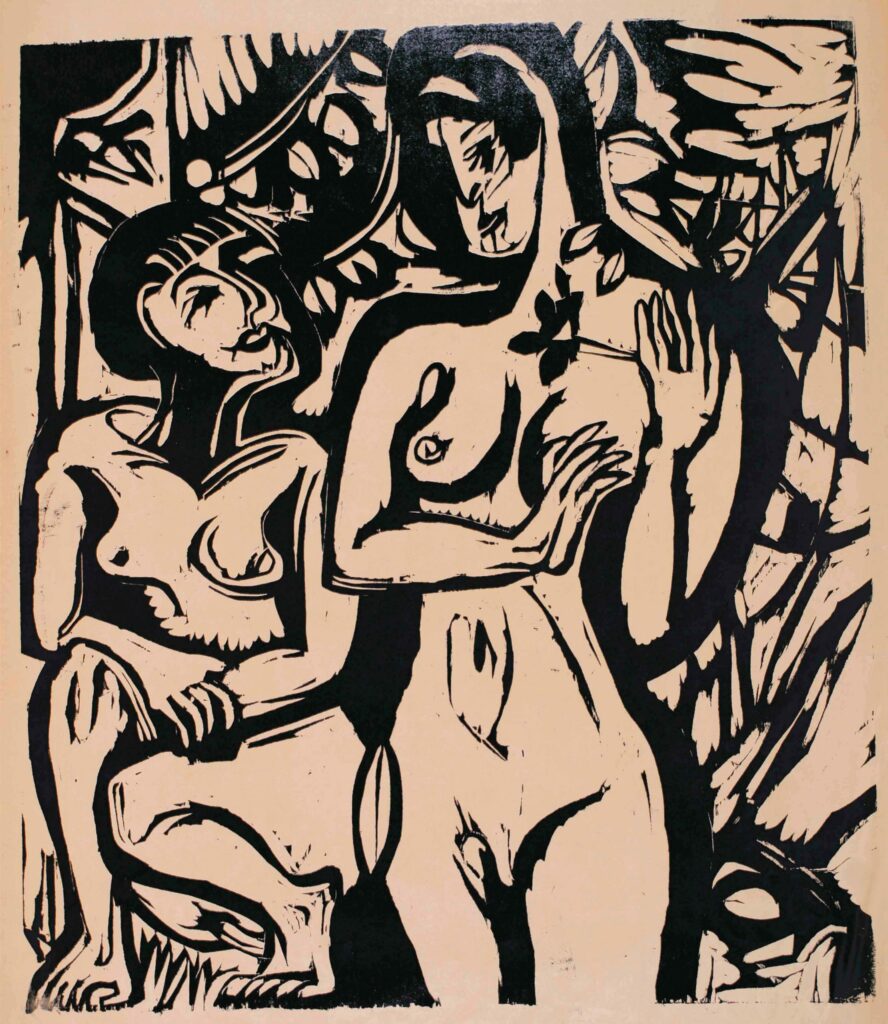

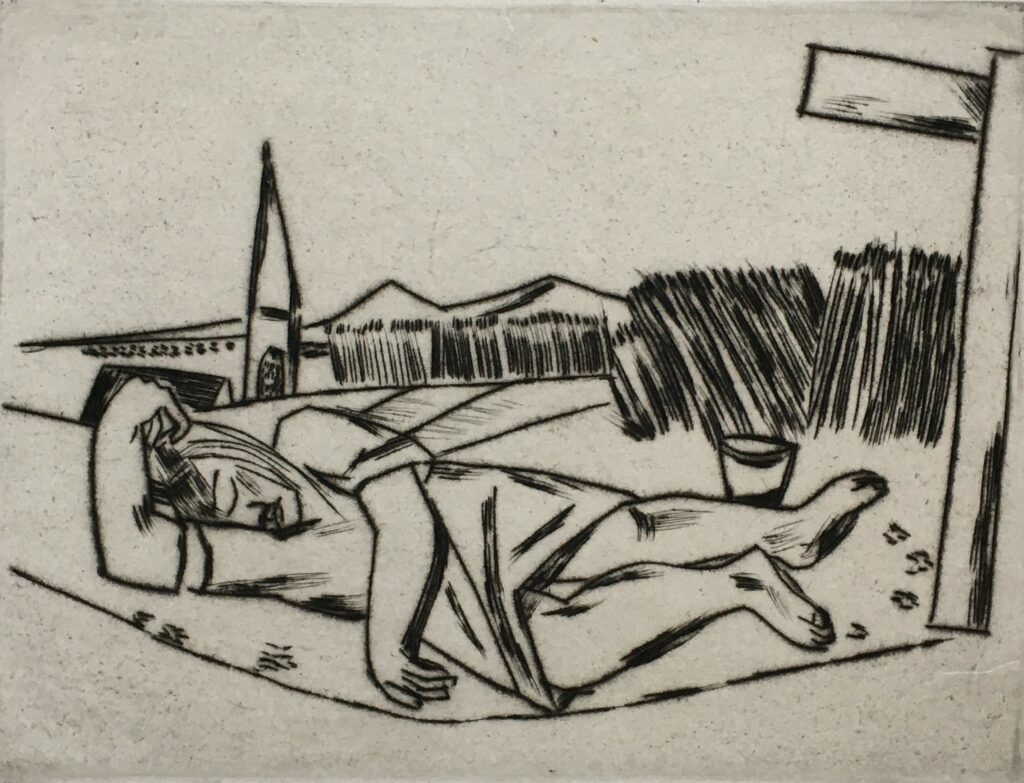

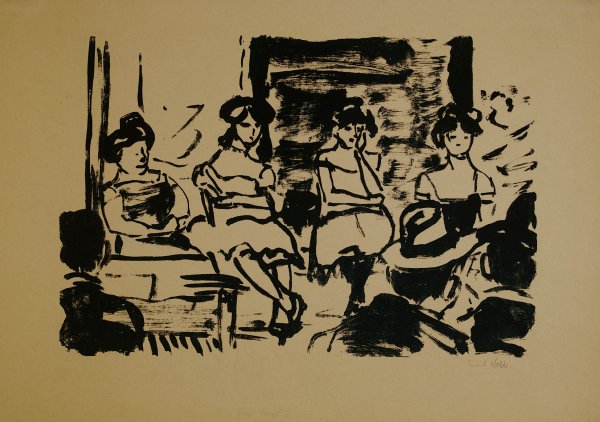

The Nazi regime primarily targeted expressionism, cubism, dada, surrealism, and other avant-garde movements under the banner of degenerate art. These modernist styles were condemned for their departure from classical artistic ideals, their emotional intensity, and their perceived rejection of traditional beauty. Abstract art was particularly vilified, as it didn’t conform to the regime’s preference for realistic, idealized representations of German life and people. The works of artists like Max Beckmann, Emil Nolde, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Max Ernst, and Paul Klee were systematically removed from German museums and publicly ridiculed.

The 1937 Degenerate Art Exhibition

The infamous Entartete Kunst exhibition, opened in Munich in 1937, represents the culmination of the Nazi campaign against modern art. Designed as a showcase of “cultural horror,” the exhibition displayed approximately 650 confiscated artworks in a deliberately chaotic and cramped manner. The works were accompanied by mocking labels and graffiti-like slogans that encouraged visitors to ridicule the art. Ironically, this exhibition drew over two million visitors, far more than the simultaneous “Great German Art Exhibition” that showcased Nazi-approved classical and realistic works.

Impact on Artists and Collections

The classification of artwork as “degenerate” had devastating consequences for artists and art institutions. Many artists were dismissed from teaching positions, prohibited from exhibiting or selling their work, and forced into exile. Some, like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, were driven to suicide. German museums were systematically purged of modern art, with thousands of works either destroyed, sold abroad, or hidden awa including artworks by Pablo Picasso and Joan Miró. This cultural purge represented one of the most significant acts of state-sponsored artistic censorship in modern history.

The Art Market and International Response

The Nazi campaign against degenerate art had complex repercussions for the international art market. While some works were destroyed, others were sold at auction in Switzerland and elsewhere, often at deeply discounted prices. This dispersion of modernist masterpieces significantly influenced the development of modern art collections worldwide, particularly in the United States. Museums and collectors abroad sometimes took advantage of the situation to acquire important works, though many also worked to help persecuted artists and preserve threatened artwork.

Artistic Resistance and Underground Movements

Despite the oppressive cultural climate, some artists continued to work in modernist styles privately or in exile. The experience of persecution and exile profoundly influenced their work, leading to new artistic expressions of trauma, resistance, and cultural identity. Some artists who remained in Germany developed coded visual languages to express their opposition to the regime while avoiding direct confrontation.

Post-War Legacy and Restitution

The aftermath of the Nazi campaign against degenerate art continues to influence the art world today. Many works remain lost or in disputed ownership, leading to complex legal battles over restitution. The systematic documentation of lost art and ongoing efforts to return works to their rightful owners has become a significant focus of museum professionals and art historians. This period serves as a powerful reminder of the vulnerability of cultural heritage to political extremism.

Contemporary Relevance and Historical Lessons

The concept of degenerate art raises important questions about artistic freedom, cultural policy, and the relationship between art and politics that remain relevant today. The Nazi campaign against modern art demonstrates how artistic expression can become a battleground for broader ideological conflicts. It serves as a warning about the dangers of using art as a tool for political propaganda and the suppression of diverse cultural expressions.

Scholarly Research and Documentation

Academic study of the degenerate art campaign has intensified in recent decades, with scholars examining newly accessible archives and documentation. This research has revealed the complex networks of collaboration and resistance among artists, dealers, and cultural institutions during the Nazi period. It has also highlighted the role of individual actors in both implementing and resisting the cultural policies of the regime.

Cultural Memory and Museum Practice

Museums today often address the history of degenerate art through specialized exhibitions and permanent collections that contextualize this dark period in art history. These presentations serve both educational and commemorative functions, helping visitors understand the relationship between artistic freedom and political power. The experience of the degenerate art campaign has profoundly influenced museum policies regarding provenance research, cultural heritage protection, and the responsibility of cultural institutions to resist political pressure.