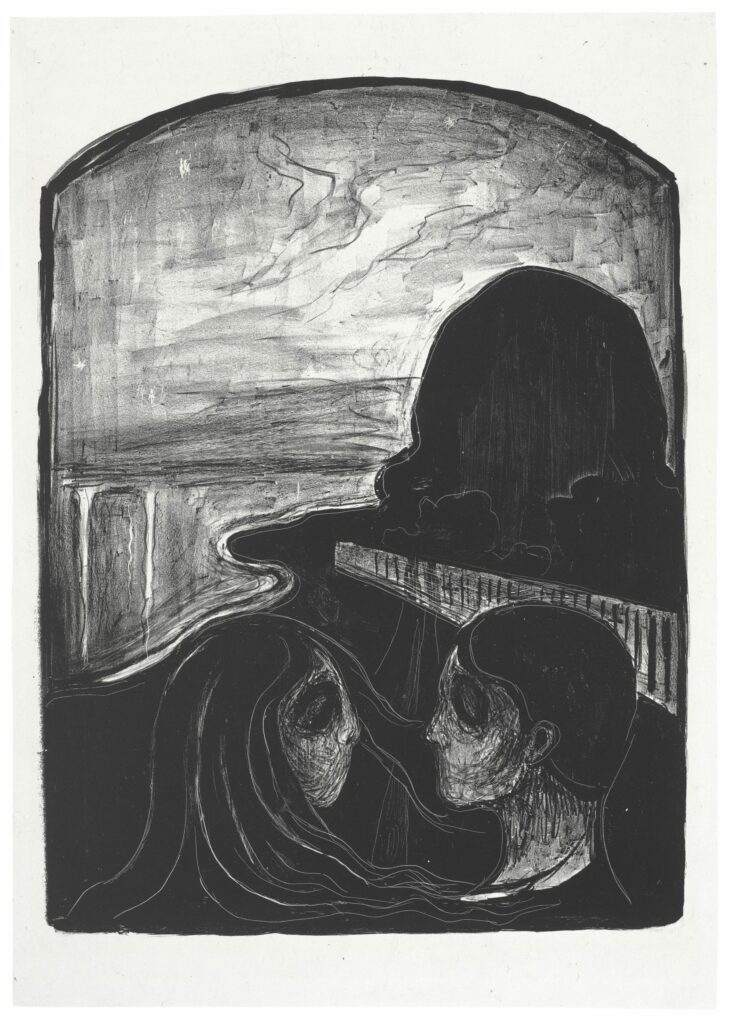

Today we’re gazing into the world presented by Attraction I. At the forefront of this gloomy and intriguing lithograph stand a woman and a man whose oddly shaped heads turn toward each other, rendering them in profile. You might have already noticed the couple’s dark and ultra-round eyes, the exaggerated taper of their noses, and their overall dreamy expressions. Together these elements imbue the entire scene with a fantastical, Gothic quality: Munch’s usually other-wordly style elevated to a new plane. The scene is shaped by a curved edge at the top, giving us a wink that this is both real and unreal, an ominous storybook page.

The subjects stare at each other hypnotically; deeper than a surface glace, it’s a look that can perceive the soul. They are sharing in the bond of attraction as the title suggests. But their eyes also reveal desperation and fear. It’s as though being drawn toward another being was something close to a curse. The moment of connection is a rapture, leading them in with a siren song promising happiness and inevitable doom.

Beyond this couple’s magnetic gaze is a winding road, leading into a mysterious distance. It curves between the choppy edges of the coastline and a towering hill. The real-life inspiration for this place might be Aasgardstrand, a port town on the western coast of Norway where Munch had newly acquired a cottage. This place was packed with meaning for Munch; it’s where he had all of his romantic firsts with Millie Thaulow, including his first kiss. These memories populated the grounds like wildflowers, the air filled with the pollen of who he used to be and who he had loved there. In his work, Aasgardstrand became a common setting to explore his romantic triumphs and heartbreaks.

Here, it’s reimagined as though in a dream, or maybe a nightmare, depicted “as a continuous strip, an uninterrupted backcloth” where “life with all its complexities of grief and joy, carries on.”* However, identifying his landscapes proves to be difficult for art historians, as his obsession with painting things as he remembered them triumphed over any semblance of realism. His psychological struggles also influenced how he perceived and recreated different natural elements. Munch was an agoraphobe and sufferer of vertigo who feared open spaces like fields and oceans. Thinking mountains could topple over at any moment and flatness might swallow him whole, he preferred the comforting density of the woods which directly surrounded his cottage. The openness in this print’s background as well as the hill/mountain can then be interpreted as a symbol of anxiety and vulnerability.

By the time of creating Attraction I, Munch had already endured the casualties of several love affairs, including the ensnaring sexual politics of his bohemian friends. Witnessing the destruction caused by reckless polyamory, money squabbles, and infidelity in his friends’ marriages, he essentially swore off the institution itself. More specifically, he referred to friend Christian Krohg as being changed from “a stout fellow” “into a slimy soft-horned snail carrying a brothel on its back”** by his tumultuous union with wife Oda. And yet, Munch couldn’t resist. He was simultaneously repulsed and drawn in, terrified of what could happen if he got too close. In this same era, he often equated kissing women, whether in a dream or in real life, to kissing a corpse. Of Tulla Larsen, his next great affair after Millie, he said “If I loved her, she would have discarded me.” He needed love, as all human beings do, but always managed to find himself with the most chaotic partners.

The stress he put himself under when around these women led to heavier drinking and subsequent bouts of physical and mental illness all while taking him away from what he truly loved the most: his art. Munch’s health always seemed to decline especially while Tulla was around. In later years, he called her “the black angel of [his] life” knowing how she used her family money and his frequent bouts of illness as bait for their relationship. The pair nearly was married in France after Munch mistakenly found himself in a binding written agreement with her to do so. He fled to Italy to avoid their union which prompted Tulla to sue him for the little money he had. During these times, Munch simultaneously loathed her and questioned his own complicity in their toxic affair, which he seemed to enjoy the thrills of as much as he resented it.

Munch’s experiences manifested in several works of his oeuvre that equate romance with a dark fate, including today’s print. He often used supernatural and Gothic overtones while exploring this theme, especially vampires. While the fanged creatures are never overtly present, there are “vampiric” elements in many of his romantic works.*** In Attraction I, the couple’s mesmorizing stare echoes the transfixing, sexually capsizing qualities of a vampire or demon. Interestingly neither party is the aggressor, nor the victim. Through a variety of symbols, Munch hints that the attraction and the destruction is mutual and inevitable.

Courtesy of John Szoke Gallery, New York.