Picasso’s Suite Vollard was a culmination of his neoclassical period in the 1930s, featuring several narrative series all heavily inspired by Greco-Roman aesthetics and values. The reclining nude was a reoccurring figure in this series, as well in other media from this era. She was almost always a stand-in for Marie-Therese, with the Suite Vollard versions being no exception. However, the soft, dream-like scene of Bloch 143 adds a different dimension to the reclining nude trope.

Typically, Picasso’s portrayals of Marie-Therese as the dormeuse strongly implied a passive role with an unseen figure actively observing her. This dynamic was grounded in the reality of their habits. Picasso would stay up late to work and Marie-Therese would doze off in the lamp-lit studio. It was his natural compulsion to find an artistic symbolism in their lived patterns, juxtaposing her angelic softness with the ferocious Minotaur, as we’ve previously seen in the Suite. She was vulnerable, innocent, and singular in her presence.

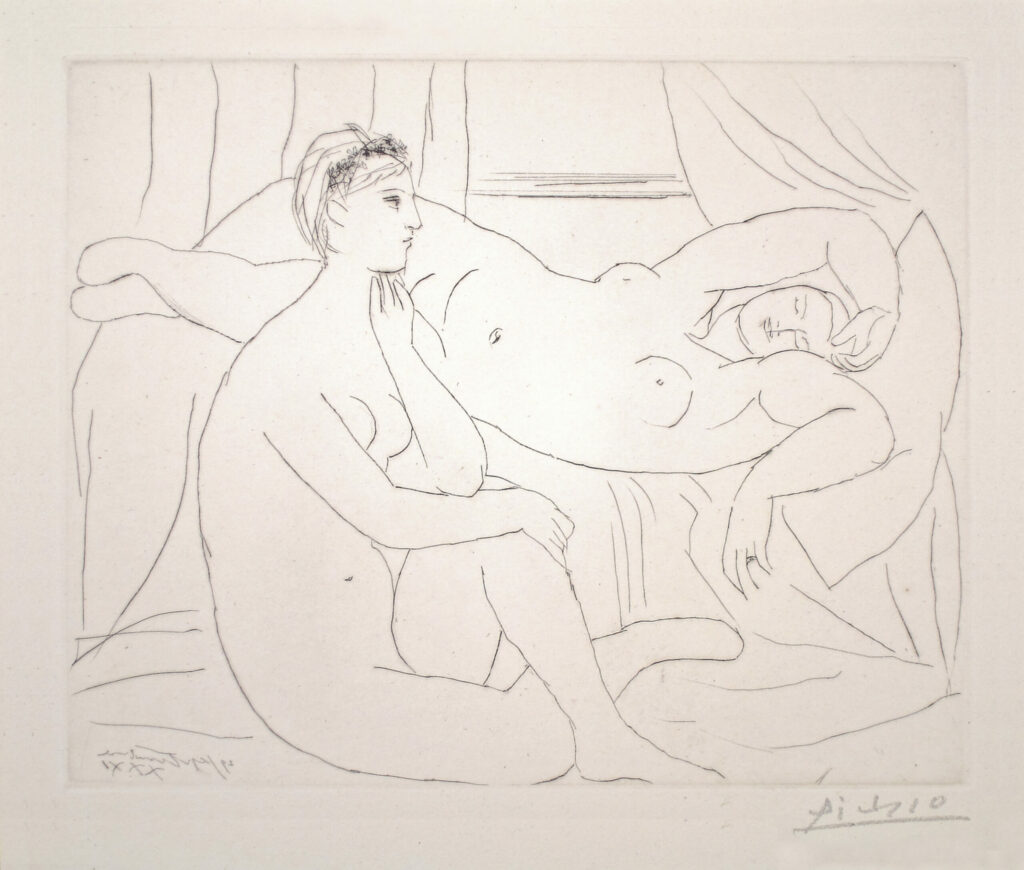

However, today’s print portrays the trope of the reclining nude woman in a world of her own. She luxuriates on a soft chaise with billowing curtains. Eyes closed, she is in complete repose. The curves of her body are both soft and muscular, not entirely unusual for Picasso’s women but unique for a Marie-Therese-inspired figure. There is more masculinity and strength to this dormeuse. She is not only the beacon of light, she is surrounded by it.

The reclining nudes who came before her were Venus figures who could be appropriately celebrated for their nudity as symbolic figures. But in the 19th century, these figures shifted from the divine to the scandalous with Ingres’ Grande Odalisque (1814) and Manet’s Olympia (1865) who were openly waiting for suitors/clients from their chaises. Picasso’s version seems to straddle both, with heavy inspiration from the ancient world’s celebration of heavenly beauty and his bold reference to his own lover. The other female figure, not sleeping but seated nearby, could be a “lady in waiting” or a servant, as in Manet’s painting of a similar scene, emphasizing the dormeuse’s regal energy no matter her actual status. Further adding to Bloch 143’s narrative is the inclusion of what could be read as a wedding band on her left hand’s ring finger.

Bloch 143 shows Picasso’s lover reclining and refracted into another dimension where she is transformed, imagined as a more confident, sexually assured woman pulled out of the darkness.

Courtesy of John Szoke Gallery, New York.