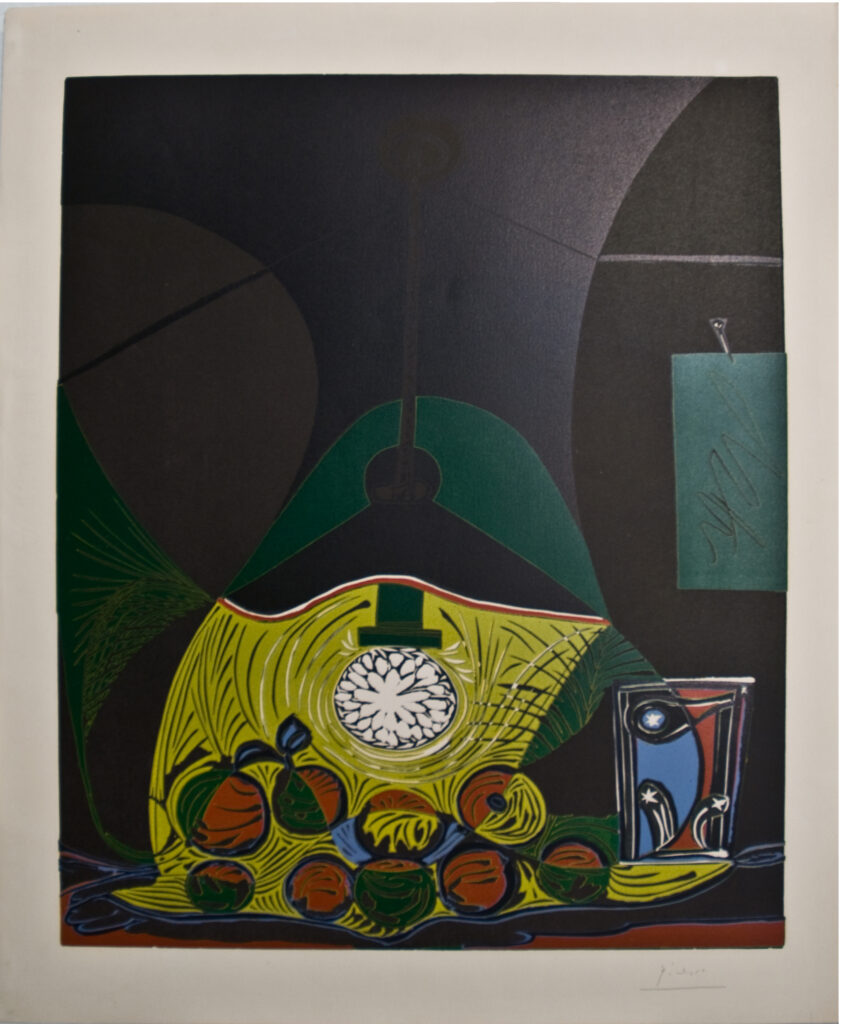

“Still Life with Suspension,” depicts a misleadingly simple scene of some fruit and a water glass on a table under a lamp. You may notice the striking contrast between the vivid primary colors illuminated by the lamp and the dense black shadow. The world under the lamp is saturated and bright; without it, there is nothing.

In a very literal sense, this scene no doubt represented Picasso’s studio, where his routine found him retreating each night, sometimes until morning. There he could disappear into the recesses of a dark, undisturbed solitude and create magic. Though this was a practice he kept for the majority of his career, by the 1960s, he had outlived many of his friends (including Cocteau and Braque) causing his social life to recede and work to take its place. Spending nearly all day and all night in the studio became the norm.

Lamps and lightbulbs also had symbolic importance throughout Picasso’s oeuvre, including Guernica’s all-seeing, exploding light. Overlooking the gore and destruction, the lightbulb seems to represent fascist oppression. In contrast with the sun, a warm, natural source of light, an incandescent bulb could be seen as an element of control, as it harnesses the elements for the sake of labor. However, there is also an immensely positive side to the lightbulb as both a real item and an artistic symbol. Electrical lighting was invented within Picasso’s lifetime and could mean everything to a person committed equally to socializing, travel, and work. At the outset of its invention, electric current was seen as a living thing with the ability to animate (i.e. Shelley’s Dr. Frankenstein using lightning to bring his monster to life). Though much less supernatural, it appears Picasso might be borrowing some of this philosophy. Here, he is the creator of the universe we’re peering into, bringing everything to life (and allowing us to see it) by way of an electrical light.

Along with depictions of lightbulbs and lamps, still life scenes are a repeated style for Picasso, though, of course, each one turns the very traditional, even stuffy, format on its ear to challenge our perception fine art and even the world at large. Here, in Bloch 1102, he manipulates the typical perspective of a still life, where the focus is on the items themselves, zooming out to show us his lighting set-up. This more technical, “behind the scenes” approach to a still life pulls us away from the hyper-realism of the genre. It makes us even more aware that this is a work of art and warps how we view the fruit, the glass of water, etc. rather than appearing to us as “real” objects. In fact, it serves to remind us that a print, like any other work of visual art, is an object itself.

Describing Picasso’s Cubist collages of the early 1900s, art historian John Golding notes the artist’s “interest in investigating the nature of solid form and of a desire to express it in a new, more thorough and comprehensive, pictorial way.” Sixty years later Picasso’s style may have evolved but his desire to explore our relationship to reality and its depictions remained strong. We see it shining through in Bloch 1102; here, Picasso presents a two-dimensional reality sliced into colors and shapes. This alternate perspective is bolstered by his choice of medium: the linocut print. Created by carving into a linoleum sheet, inking it, then rolling it through the press, a complicated and colorful scene like this one would have to be applied individually. The process is repeated for each color. Considering how segmented and detailed the illuminated area of this print is, it’s easy to imagine Picasso as the artist-as-creator-god, zapping life into each notch of the linoleum. The result: a window into a reimagined world.

Courtesy of John Szoke Gallery, New York.